For this 4th edition, we reached out to Koto Kishida, former Malaysia Program Manager at Green Empowerment and strong advocate for sustainable rural development. Through this conversation, we gained insight into Koto’s experience as a female leader working at the intersection of energy access and natural resource management.

Our conversation shed light on watershed protection and enhancement -- an important, yet undervalued, area of micro hydropower (MH), which Koto has been tirelessly working to promote. Koto recognizes that MH incentivizes communities to protect the catchment area ecosystem; by motivating watershed strengthening, micro hydro projects (MHPs) can play a key role in building climate resilience in rural communities.

Read on to learn why Koto is committed to promoting environmental conservation in community energy projects, and to gain insight into her journey as a woman energy practitioner.

My name is Koto Kishida. I am a Japanese citizen but have spent the majority of my life in the United States. In the last few years I lived in Malaysian Borneo, first as a volunteer in 2016, and then as the Malaysia Program Manager for Green Empowerment (GE) from 2017-2019. As some of the readers may know, GE is an HPNET Member, a US based NGO that works on rural sustainable development in Latin America and SE Asia. Most of the work GE has done in Malaysian Borneo has been in the area of rural sustainable development focused around energy access. GE has been supporting local NGOs such as PACOS Trust and TONIBUNG to install community based micro-hydro and solar mini-grid projects.

How did you start your career?

For most of my professional career, I worked for Oregon State's environmental protection agency, first analysing environmental samples and later working to minimize loss of forest cover and reduce polluted runoff from agricultural and forest land uses to protect water quality through policy and regulations. A large part of my work involved analyzing how much vegetation/forest cover was needed to sufficiently protect the aquatic environment. Having worked on both regulatory and voluntary programs to comply with environmental regulations, I came to understand the critical roles the local communities play in protecting the environment.

I had traveled to SE Asia in the early 2010's and was drawn to rural communities where people lived traditionally. While traveling I saw rapid development as well as emerging environmental issues. This is when I began having the desire to support local communities who had a more sustainable vision for development in their communities. I reached out to a number of NGOs that worked on environmental issues, with my desire to volunteer during my sabbatical planned in 2016. One of the NGOs I contacted was Green Empowerment. At the time, GE was working with its main partner organization, TONIBUNG, to explore opportunities to access funds for conservation. In 2016 I traveled to Sabah in Malaysian Borneo to develop TONIBUNG's monitoring program as GE's volunteer.

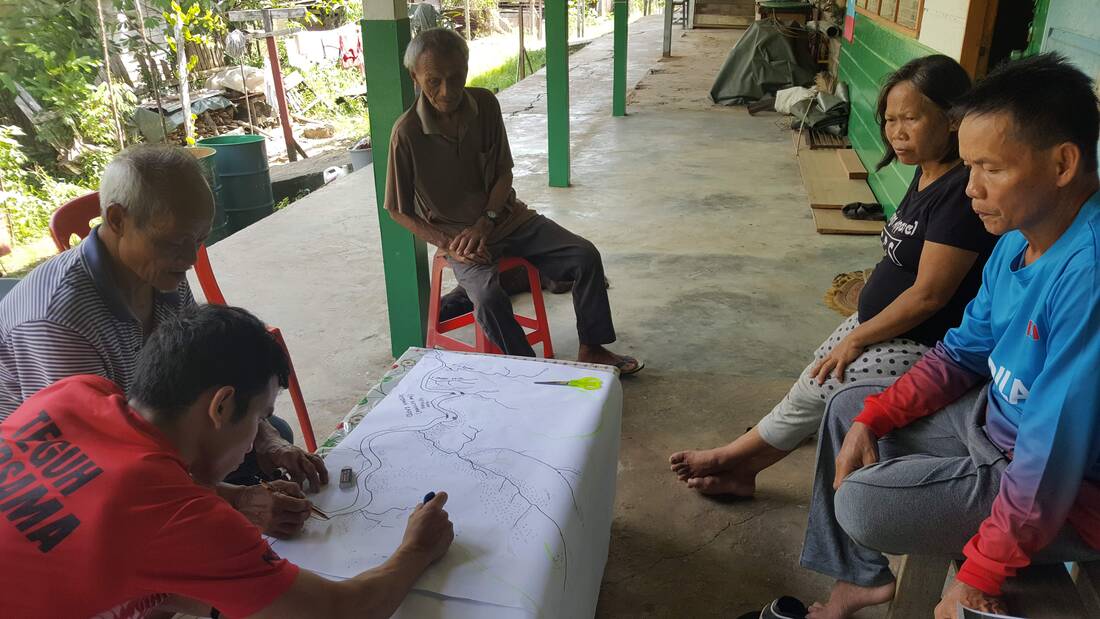

During my stay in Malaysian Borneo working with rural communities, I saw the day-to-day as well as long term struggles indigenous people faced there. My main take-away from the experience in Malaysian Borneo was the same as I had learned in Oregon — the success of conservation efforts depended on the local people's desire and ability to continue living in their community in a sustainable manner. There is a need to create a space for the community members to figure out the future they want for themselves. Our only role as practitioners is to facilitate the discussion and provide support as requested by the community.

I just wrapped up my stay in Malaysian Borneo as the program manager for GE. While there, I supported TONIBUNG in a number of ways, including fundraising, project management, overseeing budget, and advising on organizational structure and policies. While I was able to contribute, I learned so much more from the experience. I will never forget the privilege of having been given a chance to work closely with a number of indigenous-led organizations that are fighting to defend and honor the rights of its people during one of the major shifts in Malaysia's politics.

In the past few years, TONIBUNG mostly worked with two types of funding sources -- CSR funded solar/micro-hydro hybrid projects with a focus on local social enterprise development, and grant funded micro-hydro projects with an emphasis on climate change mitigation through conservation of forests.

TONIBUNG has installed 30+ community-based MH systems in Malaysian Borneo since early 2000’s. Based on the insufficient flow during the dry season for some of the communities, TONIBUNG began installing solar and micro-hydro hybrid systems for some of the communities in Malaysian Borneo starting in 2015. Where there is sufficient flow, they still install MH only systems as well.

TONIBUNG and GE had been able to access funds to build community MH systems by highlighting the inherent conservation values of such projects on the surrounding forest lands. Unlike solar mini-grid projects, MHPs motivate communities to protect their forests as source water. Because intact forest cover can mitigate for the seasonal variability of stream flow, communities have added incentive and tend to keep the forest cover upstream of their MHP intakes. I was able to continue building on their success and continue to bring conservation project funds to finance MHPs.

I left Malaysian Borneo recently and returned to the US. I hope to continue supporting MH practitioners through research and fundraising, focused on securing dedicated funds for conservation for MHPs for HPNET and GE.

As with GE's Malaysian partner organizations, I have learned that holistic MH projects are inherently better than projects that focus just on constructing infrastructure. There is also an increased need for dedicated funds to prioritize conservation activities for MHP watersheds with communities already experiencing the impact of climate change. Community members in Malaysian Borneo and practitioners from other countries have shared with me that seasonal variability in flow and erosion from land use have had negative impact on operation of MHPs. Intact forest cover creates climate resiliency, could extend flow during the dry season, and can mitigate sedimentation issues.

Unfortunately, when conservation is a budget line item, there are many ways for the funds to be spent on other important activities or materials for the project. For almost all of the projects I was involved with, at least a portion of funds set aside for conservation related activities were spent on transportation or construction of RE systems. It has always been important to address watershed management as part of community-based MH projects, and I understand that the need for it is greater than ever.

A key challenge I’ve encountered is developing effective ways to demonstrate and communicate the ecological value of MH projects.

In order to evaluate the effectiveness of certain practices, programs, or strategies, we need to establish the baseline and status of certain metrics. Within the context of community-based MHPs, quantifying ecological benefit of micro-hydro systems requires interest and commitment by the communities to collect data and have them analyzed, dedicated multi-year funding, and discipline/support from NGOs to continue the effort over time.

Based on my experiences in both Oregon and Malaysian Borneo, I’ve come to understand that agreement and commitment around monitoring don’t come about quickly. For MHPs, it’s difficult to ask people to think beyond construction of the energy system, which is already very challenging. While communities may develop and comply to regulations for watershed protection (e.g. logging is prohibited in the catchment area), documentation is another level of commitment, beyond not breaking the rules. Sustainable restoration initiatives require incentive, such as tangible evidence of the benefits of such activities; evidence requires time and consistent monitoring, which, in turn, requires funding.

There is a difference between passive eco restoration and active watershed strengthening. We can assume that passive restoration results from MHPs in the sense that, if communities are compelled to leave the catchment area alone, the resulting natural progression (i.e. of trees maturing) is a desirable outcome in itself, even if there is no active attempt at ‘enhancement’. If this is not good enough evidence to garner support, we’re stuck; unless we can find a funder who is willing to fund semi-long term monitoring, we won’t be able to attain more specific evidence of the ecological benefit of MHPs.

That said, this prioritization of quantitative data and scientific methods is a very Westernized approach. Just as international funders may be biased against local actors who lack strong English writing skills, accepting only evaluation standards set by Western funders may prevent indigenous practitioners from accessing funding. So another key challenge I’ve been faced with is this problem of colonialism within international development; there’s a real need to decolonize research methods and develop more inclusive approaches, which place value on indigenous methodologies.

Opportunity, Leadership, Long Term, Investment

Many of the rural communities that lack energy access are often facing other challenges such as lack of or limited economic opportunity, access to education and health care. There is a need and opportunity to listen to diverse opinions and insights of community members to have the best chance at success. Holistic community energy projects that aim to also address these challenges provide space for the communities to discuss their collective desires and long term goals.

Our partners in Malaysian Borneo working on energy access projects understand the opportunity these projects provide as an organizing tool for communities and to develop leadership skills. Where the communities embraced the opportunity to build micro-hydro committees that are gender balanced, I saw that they tended to have better management of the MHPs in general, with good documentation. I have also seen some women assume leadership roles within their community beyond the management of the MHPs, such as being a village head or a part of JKKK, village development and security committee. These outcomes are not realized quickly - and community members may not connect the dots and credit the efforts to engage all community members put in many years ago.

I did not make a significant impact on addressing the gender issues while working with TONIBUNG, other than some isolated successes. I have tried to understand the reasons why certain jobs are filled by men only, and challenges women face at the workplace, in order to understand my priorities for how to address these challenges. For TONIBUNG, I encouraged their staff to be inclusive of women when working with communities, and questioned their sexist comments or jokes when I heard them. I also participate in groups and discussions with others who raise gender issues, and promote local and indigenous women to speak at professional conferences.

My hope for energy sector organizations is to evaluate their operation and understand the reasons if and why men dominate their workplace, and think of ways to address those root causes. Most likely training should be provided to all staff so there is a mutual understanding around what is considered sexual harassment, gender bias, and unacceptable behavior within the organization. Without these understandings and willingness by the organization to commit to these policies, it would be difficult for women to thrive in any organization.

As far as working with communities, as I mentioned earlier, GE’s partner organizations such as PACOS Trust and TONIBUNG already understand the value of engaging women and youths. In addition to working with the elders and men who tend to be in leadership positions more often, they make an effort to engage all community members when working on a community project. As a non-indigenous, non-local practitioner, I try to be careful especially in communities as not to overstep my place as an outsider with limited understanding and experience of the local context. As much as I would like the best outcome for the communities, I do not want to force my agenda or values. Rather, while I am in the communities I fold in success stories with female leadership in conversation, and definitely make a point of spending more time with women outside of formal meetings and work parties to build relationships, but mainly to listen to what’s on their minds. Even though my time in the communities is limited, it gives me a sense of what’s important for the women.

For men, I would encourage them to check their gut feelings and thoughts for potential biases. If they find themselves doubting opinions of their female colleagues or community members, I would like them to consider what if the idea came from someone else, perhaps a male colleague. Would their gut feelings or opinions be the same? Rather than shutting down ideas, I would challenge them to fully explore their female colleagues' ideas.

For women, I would encourage them to support their own ideas and opinions, even if their colleagues are dismissive of their ideas. I would also encourage them to seek a supportive peer group outside of their organization but still within the energy sector. I think this is a good survival strategy in any sector.

For Western, non-indigenous men and women entering the sector, I would encourage them to consider what biases, expectations or assumptions they may carry with them as they enter unfamiliar contexts. It is important to continuously reflect on your positionality and centre local voices, in order to build healthy relationships and successful community development projects.