Mr. Tarek Ketelsen, Director General of the Australia Mekong Partnership for Environmental Resources and Energy Systems (AMPERES) and a member of HPNET, supported the design of the event. The HPNET Secretariat was invited to take part and facilitated the participation of HPNET members Ms. Nalori Chakma, Advocacy Officer at the Right Energy Partnership (REP) and Ms. Jade Angngalao, Area Coordinator at the Department of Social Welfare and Development through PAyapa at MAsaganang PamayaNAn (PAMANA), who has supported micro hydro efforts in her community and other Kalinga communities in the Philippines.

During the two-day dialogue, speakers shared various perspectives and insights regarding the regional context of the energy transition, its challenges, and potential opportunities, with an emphasis on social justice and inclusion.

Civil society and academic stakeholders from across the ASEAN region provided inputs during the workshop which contributed to the development of a policy brief intended to inform policy development relating to ASEAN’s commitment to net zero emissions. Chiefly, the policy brief presents a path forward to ensure the achievement of a socially equitable energy transition in the ASEAN region. The policy brief was subsequently presented by an Oxfam member during the ASEAN Summit which took place in Phnom Penh in November, and will be disseminated at other ASEAN gatherings and events where different government leaders and stakeholders are present.

A Spotlight on Social Equity for a Just Transition

In an insightful op-ed published by Oxfam Cambodia following the regional dialogue, the author emphasizes that, “with its principle of cooperation and mutual benefit, ASEAN could become a global leader by promoting a just energy transition that does not compound existing inequalities and leaves no one behind”.

This risk of compounding existing inequalities was addressed by several participants at the regional dialogue, including Ms. Chakma of REP, who flagged a threat around land grabbing that has been linked to mining for lithium-ion batteries for solar PV electricity in parts of India and the United States. As governments ramp up production of lithium to meet clean energy goals, REP emphasizes the need to uphold the rights of Indigenous Peoples, as well as elevate alternative clean energy technologies like small-scale hydropower, which has been increasingly sidelined as solar PV has taken centre stage.

In addition, a key element of the dialogue was the potential – and ethical imperative – to dovetail the rollout of clean energy infrastructure with rural electrification through an approach that empowers marginalized communities. Ms. Angangalo highlighted that Indigenous and local communities have long been leaders in this field, leveraging renewable energy within community-based efforts to facilitate energy access. It is critical that ‘last mile’ communities are centered in the ASEAN clean energy transition, and SDG 7 is prioritized within pathways to ‘net zero’.

The dialogue thus underscored the opportunity to elevate decentralized renewable energy (DRE) as a key component of a just transition. Participants brought forth a number of policy solutions to advance this aim. For instance, Ms. Chakma of REP suggested subsidies and soft loans to communities, and support directed to productive-end-use to help sustain DRE systems. She and others, including Mr. Ketelsen of AMPERES, also noted that as countries develop policies to support grid interconnection of DRE, a key part of a just transition is ensuring that communities in ASEAN have the opportunity to generate income from selling electricity to the grid. (To learn more on this topic, see HPNET’s Grid Interconnection Work Stream).

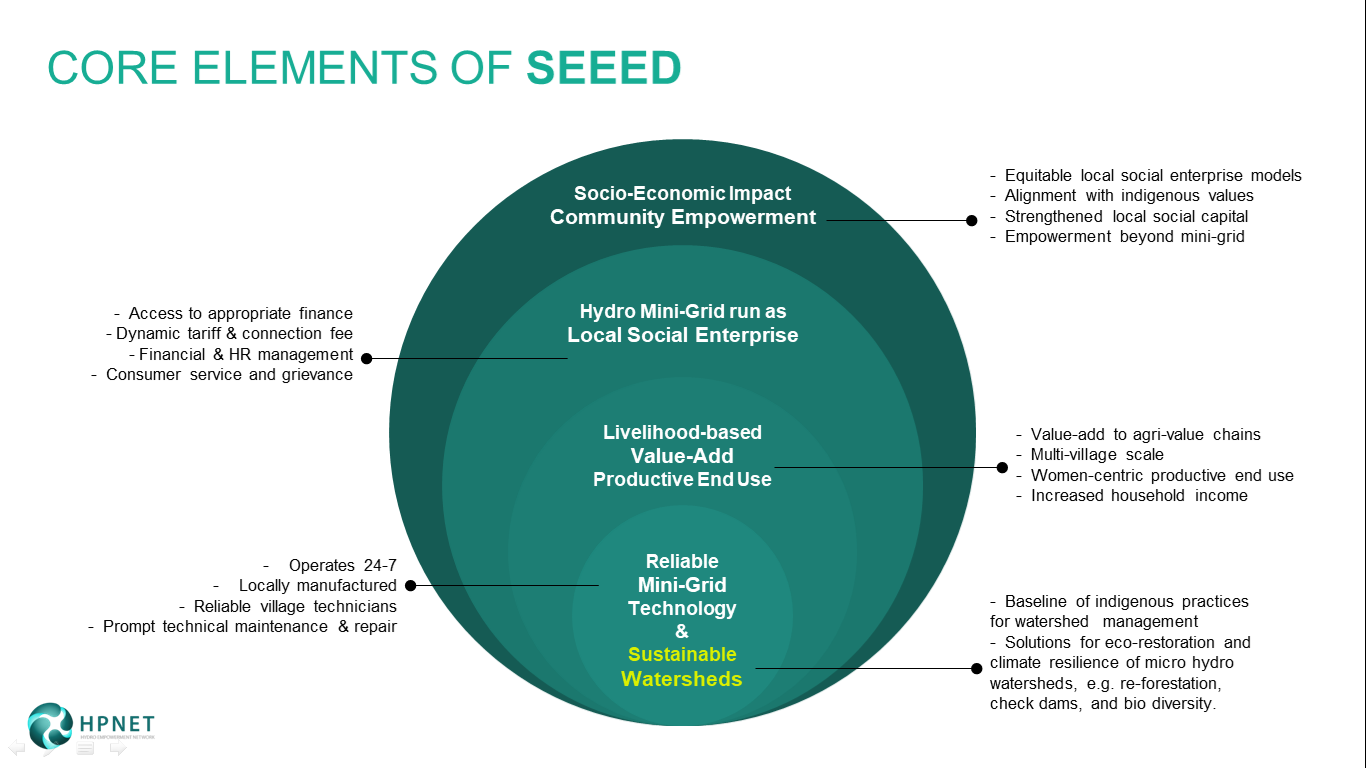

Community-scale hydropower became a focal point of several discussions, largely thanks to presentations and inputs by the HPNET members. During the Roundtable discussions, participants discussed several ways in which community hydro is uniquely well positioned for advancing a just, clean energy transition in the region.

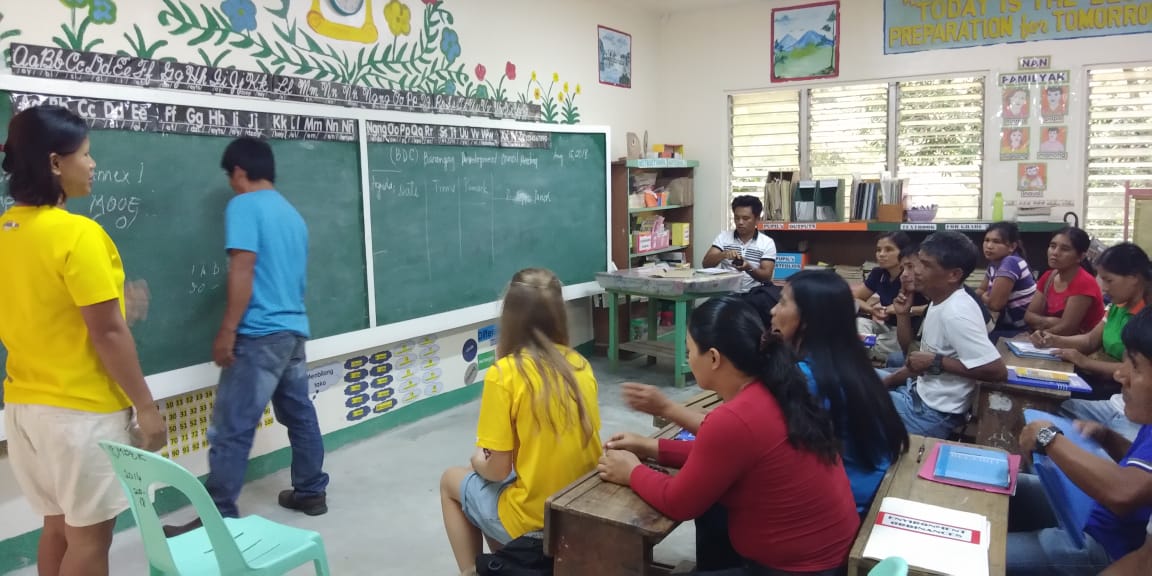

- Ms. Angngalao delivered a presentation on community-based renewable energy systems andIndigenous Peoples in the Philippines and introduced HPNET’s knowledge exchange and advocacy initiatives. The presentation highlighted how community hydro is collectively built and operated, and generates a wide range of socio-economic and ecological benefits. For instance, micro hydro can support motorized loads for agro-processing and incentivizes sustainable watershed stewardship aligned with Indigenous governance traditions.

- Given said connections with environmental conservation, Ms. Chakma or REP also noted the opportunity for micro hydro communities to leverage conservation finance and carbon credits for forest management.

- Ms. Chakma also highlighted that community-scale hydropower sidesteps the human rights and land grabbing issues arising in connection with lithium-ion batteries used for solar PV systems. (Notably, a clear distinction was drawn between small-scale (< 1MW) versus large scale hydropower dams, the latter of which have long been associated with land grabbing and ecological harm, though sometimes promoted as “clean energy”.)

- Mr. Ketelsen of AMPERES imparted some of the best practices and opportunities observed in Myanmar, a country with a long-established, locally-rooted DRE sector where over 6,000 small-scale hydropower systems have been installed by local developers, largely without donor support or foreign technology. Mr. Ketelsen observed that that micro hydro is a particularly well-suited technology for enabling more inclusive, community-owned and -distributed systems, due to unique governance and scale aspects.

The great value-add of community hydro was well-noted by other participants who expressed interest in intra-regional exposure visits to share knowledge and build awareness of micro hydro amongst ASEAN energy access practitioners and proponents – in line with HPNET’s approach to peer-to-peer exchange and knowledge exchange.