If you missed joining the event virtually, their presentations and others are now available at the links below!

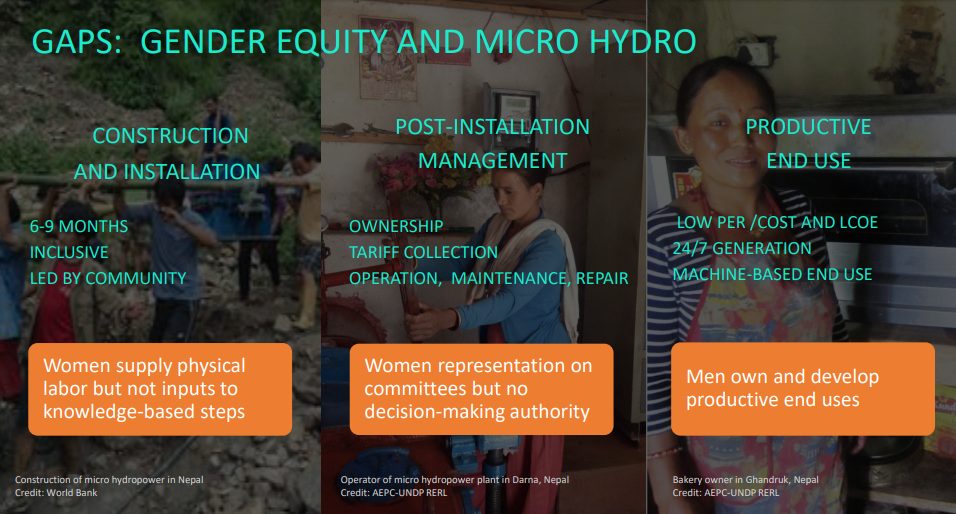

Mr. Satish Gautam, National Programme Manager of the Renewable Energy for Rural Livelihoods initiative of Alternative Energy Promotion Centre (AEPC) and the UNDP in Nepal, presented the drivers that led to the scaled dissemination of micro hydro in Nepal. Watch here (Apologies, the event organizer's link to this presentation no longer works).

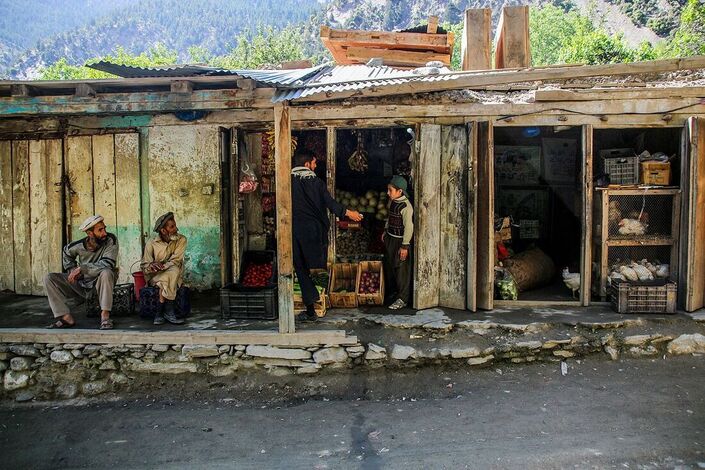

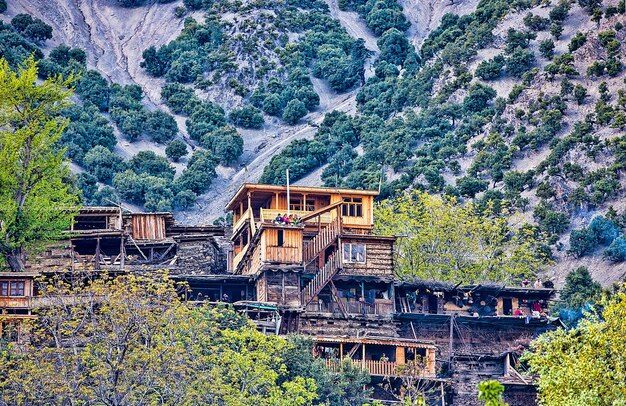

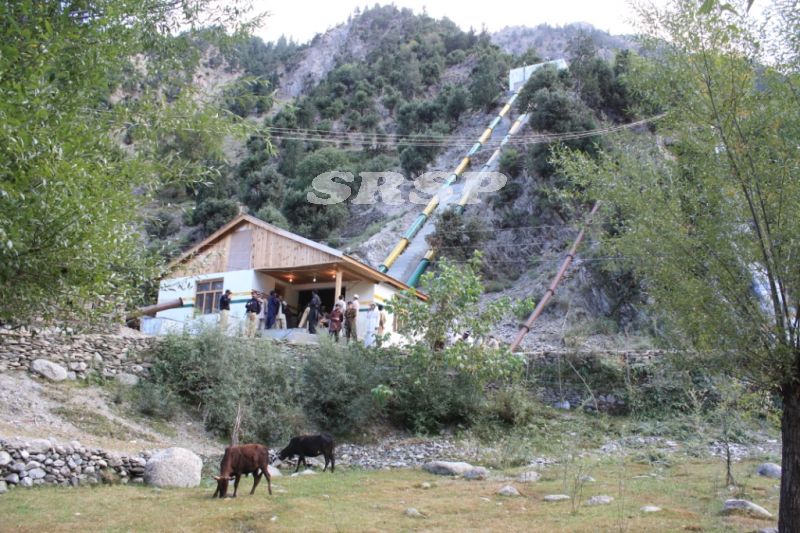

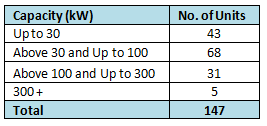

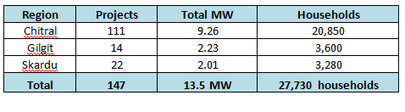

Mr. Sherzad Ali Khan, Regional Coordinator of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN) in Pakistan presented cases of community-driven enterprise solutions for micro and mini hydro sustainability. Watch here

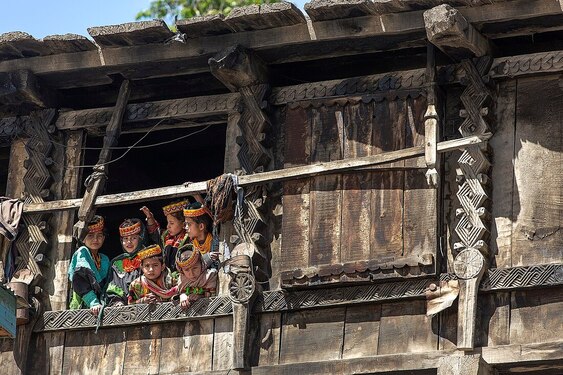

Ms. Jade Angngalao, Indigenous People's Energy Access Specialist in the Philippines presented on the role of Indigenous Knowledge and governance traditions in climate resilient solutions for hydro mini-grids. Watch here