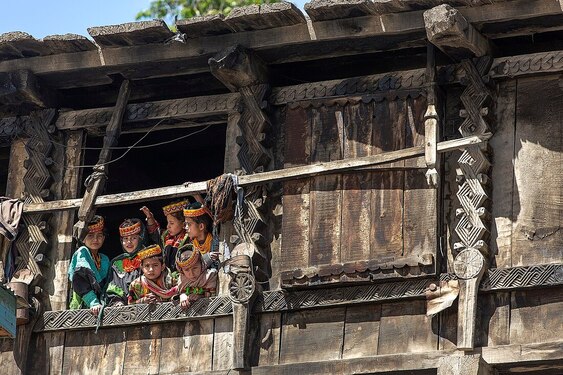

Building onto our Earth Voices series, which featured case studies of Indigenous communities who have developed resilient hydro mini-grids through watershed stewardship, we now go further to understand how rural energy systems can benefit from Indigenous values and methods for climate resilience. We aim to do this by facilitating dialogue with Indigenous leaders and organizations seeking to integrate traditional knowledge and values into energy access solutions.

As a start, in the kick-off of our recent SEEED E-Learning course, “Climate Resilient Solutions to Hydro Mini-Grids”, we were privileged to be joined by Hon. Adrian Banie Lasimbang, Advisor for TONIBUNG and JOAS and Board Member for the Right Energy Partnership (REP) and HPNET. Watch the recording for a deep dive discussion on climate resilience, the water-energy-food-forests-livelihoods nexus, and Indigenous rights, traditional knowledge and stewardship protocols.

The course was the second in our E-Learning series, offered as part of the SEEED Accelerator, with support from Skat Foundation, DGRV, GIZ, and WISIONS.

- To learn more about the ways in which Indigenous knowledge and environmental governance supports healthy watersheds and sustainable hydro mini-grids, check out our Earth Voices blog series.

- To stay in-the-know regarding future E-Learning opportunities, sign up for our newsletter.

- To learn more about Right Energy Partnership, visit their website.