- the improvement of the regulatory framework for renewable energies (RE) and energy efficiency (EE);

- vocational training and university education;

- the establishment of service agreements for private owners of RE systems and finally;

- rural electrification of micro and small enterprises (MSE) in the productive use of renewable energy.

|

Decades of civil war have hindered energy infrastructure development in Afghanistan, particularly in rural regions, where 74% of the country’s population resides. Yet, more than 5000 hydro mini-grids were installed in Afghanistan between 2003 and 2015, vastly expanding rural energy access. The majority of these systems are community-owned and -managed, many are self-financed, and nearly all utilize local technology. (For a detailed overview of renewable energy potential and community-based projects in Afghanistan, see this presentation by HPNET member, Sultan Javid.) Over time, micro hydro manufacturing capacity has developed in many regions of Afghanistan, thanks to the ingenuity of local entrepreneurs and the contributions of organizations like HPNET member Remote HydroLight (RHL). Through training and technical support, RHL supported communities seeking to manufacture, install and maintain turbines and electric load controllers (ELCs), from 2006 until 2013. RHL and the International Assistance Mission, which RHL’s founders were involved with prior, supported the installation of about 400 hydro mini-grids in total. Reliable, locally manufactured technology is a foundational element of hydro mini-grid sustainability and community empowerment. For this reason, local technical capacity is prioritized in our SEEED initiative, which supports practitioners and communities to transition toward long-lived hydro mini-grids anchored in local social enterprise. By supporting technical capacity-building, practitioners like RHL can support local actors to achieve sustainable hydro mini-grids and lasting community empowerment. Indeed, although RHL discontinued activities in-country in 2013, many systems that were supported by RHL are still in operation after over a decade, thanks to RHL’s efforts to build the capacity and technical know-how of local workshops. International donors are also stepping up to support the sustainability of small-scale hydropower in Afghanistan. This year, Skat Consulting Ltd. is collaborating with GIZ to assess 400-500 projects for rehabilitation. Assessment will focus on technical aspects, as well as productive end use, which is another critical element of mini-grid sustainability. Read on to hear more about the initiative from Skat consultant and HPNET BoA Member, Dr. Hedi Feibel. Small-scale Hydro and PV Rural Enterprise in Afghanistan The GIZ Energy Sector Improvement Program (ESIP) in Afghanistan, under its four objectives, supports: Under the fourth component, an “RE survey tool” has been developed to assess the current situation in the three provinces of Badakhshan, Takhar and Bamyan with regard to their RE supply and possible improvement, in particular for enterprises and their productive use of energy. The tool is an excel file which is filled with data and information collected by the local team of more than 30 experts of a joint venture between VOLTAF and SH Consultants. Before and during the survey, the local team is supported and guided by the mini hydro experts of Skat Consulting Ltd. and a solar expert of intec-gopa. The international consultants mainly act as external data evaluators, quality assurers and technical solution advisers on data collected from the national team during the survey. During the tough winter months, the team started the survey and provided valuable data, information and photos. The collected information will be condensed in various types of “fact sheets” (e.g. district fact sheets, MHP fact sheets, etc.) to finally assess, evaluate and select energy systems to be rehabilitated (MHP systems) or newly installed (solar PV systems), to increase income generation in MSEs that guarantee cost-covering operation of the RE systems in rural areas. The approximately 400-500 MHP fact sheets will summarise the technical and managerial status of the schemes to quickly assess the potential for improvement. Guest blog post written by HPNET Board of Advisors member Hedi Feibel, PhD, of Skat Consulting Ltd., with introduction inputs from Owen Schumacher of Remote HydroLight.

2 Comments

Based on regional hindsight and best practices from local practitioners, we have identified several core elements that enable hydro mini-grid sustainability; these interlinking elements provide the basis for our initiative Social Enterprise for Energy, Ecological and Economic Development (SEEED). Sustainable watersheds are the foundational element of SEEED because hydro mini-grids rely on, and can contribute to, the health of forest landscapes. Healthy forested watersheds support consistent flow year-round, mitigate erosion and landslides, and contribute to climate resilience. Small-scale hydropower can incentivize communities to tap into and revive traditional ecological knowledge, in order to protect and restore watersheds and enable reliable energy access. (See our Earth Voices feature series for examples of indigenous communities that are harnessing the interconnected benefits of watershed restoration and small-scale hydro.) To better understand best practices for integrating watershed restoration and community hydropower, we look to insights from Nicaragua. In the video presentation provided below, we had the privilege to present the exemplary work of the Rural Development Workers Association Benjamin Linder (or ATDER-BL) and the Association for the Development of Electrical Service in Bocay (or APRODELBO). ATDER-BL and APRODELBO have been advancing rural energy access in Nicaragua since 1987, while restoring many acres of watersheds in partnership with local communities. We hope that the presentation will inform and inspire watershed restoration efforts among practitioners, elsewhere. Presentation developed by ATDER-BL, APRODELBO and HPNET

Presented by HPNET Secretariat member Jorge Nieto Jiménez For nearly three decades, Yamog Renewable Energy Development Group Inc. has been advancing clean energy solutions to improve socio-economic and environmental well-being in rural Mindanao, Philippines. Yamog’s holistic approach prioritizes local capacity building, watershed restoration and sustainable development—resulting in sustainable projects with high value-add that illustrate the wide-reaching potential of community-based, small-scale hydropower. Keep up to date on Yamog’s impactful work by liking their Facebook page where they frequently post insightful and inspiring updates. A quick scroll reveals just how active the organization is — leading watershed resource mapping, facilitating workshops to build local technical capacity, supporting women-led enterprises, and so much more. Be sure to hit the ‘like’ button and show your support for Yamog’s dedicated efforts to advance sustainable, community-led development. Our Hidden No More series features women micro hydro practitioners who have transformed gender barriers to generate energy access for marginalized communities.

But you really cannot ignore the environmental impact of oil and gas extraction. I got to witness firsthand how damaging drilling is to the environment. Even though I appreciated the opportunity to travel and work with a diverse group of people, I realized pretty quickly that oil and gas wasn’t for me. I then found myself in Somaliland in the Horn of Africa where I was a volunteer teacher at a school. The school was putting up a 20kW wind turbine, the first one in the country. I supported the first phase of the project - putting in the foundation for the turbine- my first experience with renewable energy. I realized that I could still utilize my engineering background and work in international development. That was really how I came to learn about the energy access world. Wanting to get more experience with renewable energy systems, I spent a summer with my first micro-hydro project in Malaysia - supported by a then professor at the Masdar Institute (now my co-founder and colleague). When my time in Somaliland ended, I joined the Masdar Institute as a graduate researcher to continue working on community energy systems. What was your research focused on at Masdar Institute? My work at the Institute was focused on understanding the links between community development and mini-grid systems, and how you could design engineering systems differently to incorporate community development objectives. I felt like I had spent enough time studying the engineering side of things, I wanted to get creative and merge all these learnings from other non-engineering fields into engineering systems. Using the tools that we know in engineering systems and architecture, and incorporating methodologies from social sciences and anthropology. The idea was simple and definitely not new, if you looked at a system and expanded the boundaries to include all the non-engineering aspects of it, you would get a much more comprehensive system. The challenge was translating those aspects into engineering requirements that don’t dismiss the people factor.

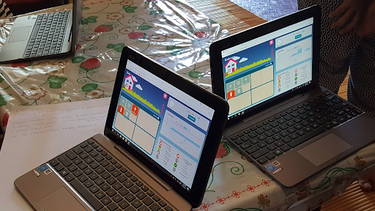

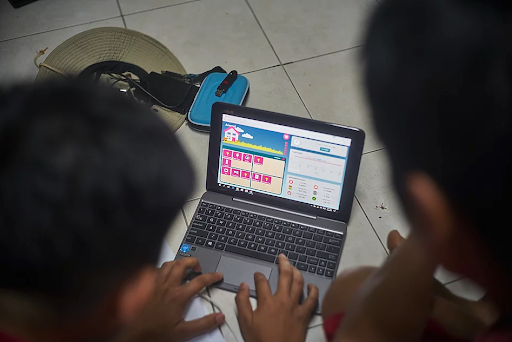

Tell us about why you established Energy Action Partners (ENACT). By the end of my time at Masdar, I was committed to the work that I was doing with community energy and wanted to take The Minigrid Game further and build it out. In 2014, with my graduate advisor and another colleague who has since left, we co-founded Energy Action Partners. In Energy Action Partners’ early days, we continued with the work we had been doing around community energy systems with The Minigrid Game, and short field-based courses for students and young professionals on energy access, community development, and social entrepreneurship. These early programs gave us the opportunity to partner with other organizations, while building up The Minigrid Game. Fast forward 6 years later, The Minigrid Game is now COMET - Community Energy Toolkit, and is very much our core program. COMET is a software tool that simulates a mini-grid system. It’s used in field-based mini-grid planning workshops to inform and engage communities through meaningful collaboration. Among other things, COMET helps communities and developers make better decisions around system sizing, tariff-setting, and demand-side management. After receiving funding from Wuppertal Institute’s WISIONS, which enabled us to conduct our first Minigrid Game (now COMET) community deployments in 2017, we started seeing interest in COMET from other organizations. Last year, we received funding from Innovate UK’s Energy Catalyst, which gave us the support we needed to take the software tool to the next level and turn it into COMET, a robust community-driven demand exploration tool for mini-grids. With our team working from home this past year, we’ve had the time to develop new features and rethink our plan to grow COMET. What's ENACT's approach to community engagement? Our approach is based on our values as an organization, heavily inspired by the Human Capability Approach from Amartya Sen. To us, community development is 1) defined by the community and not by anybody else, and 2) a set of capabilities and opportunities that communities want for themselves. Development should always be defined by the communities and not by an external entity telling them what development should look like. Our values guide us to develop micro-grid systems that meet those desired opportunities. If a community, for example, says that their set of capabilities includes wanting to be more politically active and to access more education, then the micro-grid system should enable that. It should enable television, telecommunication services, internet and all that they need so they can further their intended capabilities. And everything else may become secondary - if a system doesn’t run reliably 24/7 but still fulfils the community’s objectives and goals then that to us is still a success. Essentially, we define the objective of a system slightly differently than how others may view things, where it’s about making sure that the electricity system runs the way it was designed. I mean that’s definitely a positive, but what’s more important is the community actually achieves what they wanted to in the first place. That is key to our approach and values, and what we want to achieve. What were the gaps in community engagement 10 years ago and how have those evolved over the decade? Conventional methods involve finding a community and asking them about their needs. The question of trying to find out what they need is challenging, and depending on how you ask and who is asking, you can get very different results. For example, a conventional method for demand estimation is you engage with the community and conduct household energy audits, but as many of us in the sector acknowledge, this doesn’t always work. Demand estimation has been a tough nut to crack in mini-grid development. For off-grid communities, surveys and questionnaires don’t always make sense. Questions around what are you going to do with electricity and what things you want are very difficult questions to answer; they’re related to so many different things like income, who lives in the house, my kids are going to grow and what are they going to do, so all these questions are really difficult for people to answer directly. Some might think it’s overcomplicating the issue because electricity provision involves a technical question that can be answered with a technical solution, and that you are just trying to answer some questions with numbers; but when you are talking about electricity use, it’s about people’s behaviour, it’s not just about numbers. I think unless you have a very strong relationship with the community where you really understand what they need and what they could potentially evolve into, you are more than likely to get the wrong answers to those very technical questions. At the same time, it is really hard for organizations to spend a lot of time and build that trust and relationship with the community. So these are some of the gaps I observed and wanted to work with. There has to be some kind of process that would make it a meaningful exchange. That’s why I started looking at the field of anthropology and social science, and how they approach a community to obtain objective information. It also cannot be a one-way, extractive exchange because communities are going to receive this big piece of technology, so they are going to have to learn things, and change, and build their own capacities to manage and operate. So, it has to be a two-way exchange. The one-way process was part of the community engagement that practitioners or project developers conventionally do where they collect information and think in exchange, they will give the community electricity and that would be sufficient, but it’s not. The community really has to engage with the process as well and from the very beginning. To me, it’s a no-brainer because you get a better designed system! If engaged, people are better able to tell you what they need, what they will do with the electricity, and they are more invested in it, which leads to a higher success rate. Also 10 years ago, we saw more abandoned systems because it was so easy to fall short on the design and mis-appropriately size the system. I think now because of technological advances, we’re getting better at it and there are more options available for electrification, but it is still very much through technology and not through a people-driven process. Could you tell me a bit more about the gaps in energy access practices locally and internationally, and the shortcomings of traditional approaches? I think the gaps and the shortcomings are the same both locally and internationally. Everybody recognizes community engagement is very important, very key, but I don’t think we invest enough in processes to do it robustly. There has been very little investment going into developing and researching new approaches to the community engagement side of mini-grid development. So far, we have seen research institutes and universities come up with frameworks or a process. But framework and processes are, while they provide useful learning and outcomes, still not easy enough to scale up and deploy. And that's why as an organization, we decided to develop a tool for community engagement, focusing on demand exploration for mini-grid developers. There needs to be more effort into looking at community engagement and the opportunities, and asking ourselves how do we solve problems and gaps? We need to go further than the just fulfilling project requirements for community engagement. So far, community engagement has become the catch all phrase for any kind of engagement process but we know that there are different levels and outcomes to engagement. You can have engagement that’s one way and very extractive and you can have engagement that’s two way, but perhaps there is a lack of ownership, on the community side. What you really want is community engagement where there is ownership, there is two-way exchange, and there is capacity building happening on all sides. That’s the level of engagement we really need to push for in energy access and mini-grid deployments. How has your experience been overall as a female professional in the energy space?

Once I could actually put language to it, I started realizing more and more that it happens more often than it should. I think I have been really lucky because I was so ignorant of it for so long and it didn’t stop me nor occur to me that it was happening to me because I was female. Although I think I was lucky; I definitely realize that isn’t the case for other women and with some women, it stops them from continuing and that’s what need to prevent from happening. I think now that I am aware of it, I can’t go back to how it was before. I see it now and can recognize when it happens to me, when somebody treats me differently just because I am female and they think I am less capable or technically incompetent. But being in the position that I am now, I am better placed to deal with it and hopefully I can do something about it too. In terms of facing those barriers, do you have thoughts on approaches to making sure that discrimination in the energy space doesn't continue?

What we don’t do is we don’t enforce gender perspectives on the community because we recognize that all the communities are at different points when talking about gender equality and equity, and we have to be sensitive to that. If communities recognize themselves as gender unequal, then we will support them wanting to find ways to make things more gender equal. But if communities don’t recognize it despite our workshops and process, then we believe it’s not our place to do anything about. That has been our approach so far. For instance, we don’t promise that there will be an equal gender ratio when we form a Village Electrification Committee, because in some cases women may not want to be involved in that capacity. However, if we find in our workshops that women want to be involved but they don’t have an opportunity, then it is important to us that we try and do something about that. If everybody is okay with the status quo, then we accept that. Yes, you can argue that acceptance is due to a lack of exposure. That may be true. But that’s why it’s also important for our team to have healthy gender balances and when communities see female teams like ours visiting them, we hope that that provides some exposure as well. But if, after this exposure and our gender workshops, they still make the decision to not do anything about things, we should respect that. What motivates you to keep on doing the work you are doing?

I really like working with communities. I think communities, and especially rural communities, have such a special role to play in the world. First of all, regardless of what governments or anybody else tells you, rural communities are on the front line of renewable energy and the transition. Unlike urban communities, rural communities don’t have much of a choice. They use decentralized renewable energy systems because they have to, and remember, off-grid communities have been using these systems way longer than urban users. I feel like that’s something that people forget, or they don’t think of. That rural communities are on the frontlines of climate change issues and the transition. And the transition to renewable energy for them is a live or die situation for survival. I learn a lot from these communities and being able to work with them is what motivates me. |

Categories

All

Archives

February 2023

|