- In 2013, International Rivers and the Nagaland Empowerment of People thru EnergyDevelopment (NEPeD) hosted a micro hydro exchange event focusing on NE India, which connected HPNET to the Meghalaya Basin Development Agency (MBDA).

- In 2015, HPNET enabled India practitioners to attend HPNET’s Members Gathering held in Indonesia at the Hydropower Competence Center (HYCOM), connecting them to Pt entec Indonesia.

- In 2016, MBDA and HPNET held a regional exchange in Meghalaya, with VillageRES and PT entec Indonesia as co-facilitators.

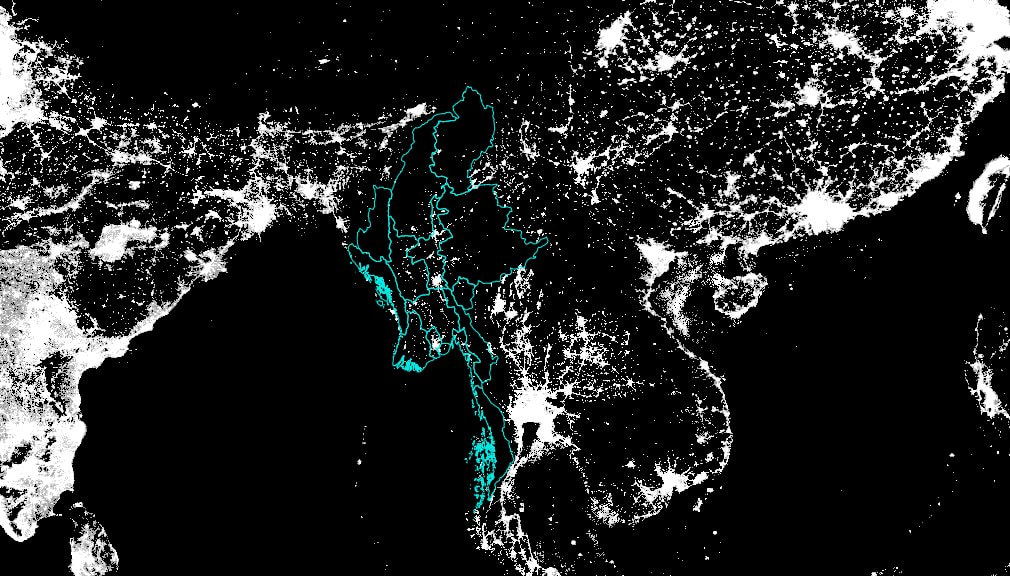

- In mid-2019, International Rivers and partners, including HPNET, hosted a tri-country dialogue in Meghalaya, with CSOs and local practitioners from Nepal, Myanmar, and India.

- In late 2019, HPNET supported a reconnaissance field visit to understand field-based challenges to pico hydro scale up in NE India.

- In 2021, HPNET and International Rivers held a three-part virtual exchange focusing on Ganges, Brahmaputra, Meghna, and Salween (GBMS) Rivers, providing regional inspiration from across S/SE Asia and customized capacity building.

- The 2021 event included a special keynote by Mr. Augustus Suting, Special Officer at MBDA.

Below Mr. Ramasubramanian Vaidhyanathan (“Rams”), who has long been committed to the sub-region, provides a brief and exciting update on the most recent technical developments brought forth by a partnership between HPNET members VillageRES and Pt entec Indonesia.

VillageRES (Village Renewable Energy Systems India Private limited) participated in the tender in partnership with EMSYS Electronics Private limited, a solar energy company based in Bangalore. The consortium was awarded 45 sites located throughout Meghalaya.

VillageRES entered into a manufacturing license agreement with PT entec Indonesia to manufacture their new cross flow turbine design with 150mm diameter runners. The turbine is called CFT 150/21.

The fabrication began in July 2022. Pt entec Director, Mr. Gerhard Fischer, and the team helped us a lot with fabricating the first few pieces – updating drawings, dimensions, a few design corrections, etc. We fabricated the units in the south Indian industrial hub of Coimbatore, in the state of Tamil Nadu.

We are very pleased with the results: the turbines have come out very well made and were cost effective to fabricate. We also tested a few of the turbines at a site in Meghalaya and the performance was fantastic. We will be assessing the performance of this model more thoroughly once all the units are installed.

He can be reached at [email protected].