Urmila Senapati. Credit: A. Behara.

Urmila Senapati. Credit: A. Behara. You can check out more Hidden No More interviews here. The series spotlights women small-scale hydro practitioners, to honour trailblazers who have made a difference in the sector and to inspire the current and next generation of women practitioners.

I started with Gram Vikas in 1986, when I was 26 years old. I worked there for 33 years, until retiring in 2019. I currently live in my native village called Raghunathour, in Jagatsingpur District in Odisha State, India. While I was working for Gram Vikas, I never thought that I would retire when I reached a certain age; I always thought that I would retire when I felt tired, but there is an enforced age for retirement that I had to follow. After retirement, many of my well-wishers invited me to continue my journey working in the sector, but unfortunately my mother’s health condition, coupled with the COVID-19 pandemic, prevented me from continuing. That said, I still try to help my colleagues with work matters over the phone sometimes.

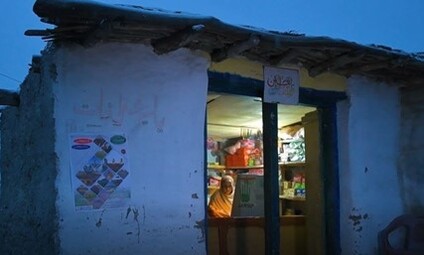

I was born and raised in Kharagpur, West Bengal up to grade 7, as my father worked for the railway department. When my grandfather passed away, my siblings and I (two boys and four girls) moved to our family’s village with my mother. We went to live with our paternal uncle, but it didn’t work out. My uncles were very powerful men in the village. They didn’t allow us to live with them nor did they give us our share of our paternal property. They harassed us and prevented me from going to school. I was 11 years old at the time. They purposefully disconnected our electricity and didn’t even allow us to buy kerosene from the shop to use for lanterns. Those incidents sparked a rebellious spirit in me. I realized how rich and powerful people treat the poor.

Under such conditions I completed my studies, and at the age of 19, I started my career as a government school teacher, but I did not continue for long. One of my cousin’s brothers, Badal, was working in the charitable sector and asked me if you I would be interested to work in the sector. The day I got the chance to work in the nonprofit sector, I immediately joined Gram Vikas as a Field Organiser in a remote tribal village under Kerandimal project, Ganjam District. During those days a typical work day included 16-17 hours of walking, often from 6:00am to 11:00pm, to engage with community members. Most of my friends criticized me, saying that I was crazy to leave my government job for this type of work, but I did not care. After that I never looked back. I grasped the opportunity to work independently and uplift the voices of poor communities to a higher level, to fight against injustice and inequality. This is the way I started my career in the nonprofit sector. Over time I held different positions with increasing responsibility, up to Senior Manager, and did my best to produce positive results in each role.

“I grasped the opportunity to work independently and uplift the voices of poor communities to a higher level, to fight against injustice and inequality."

I realized early on that water is a precious resource. In southern and western Odisha, most tribal communities are less developed than those in other parts of Odisha. They lack basic services and access to clean water, electricity, communications, food security, healthcare, etc. Most tribal people die from common diseases like diarrhoea, TB, fever and jaundice, most often impacted by waterborne diseases. Water is important for many reasons. Can you imagine that, to get a bucket of water, a woman must walk 1 to 2 kms in a mountainous area? Cooking and eating must be finished before nightfall, otherwise families must eat by the light of a fire (“chula” light). Some communities have abundant natural resources but cannot benefit from them; all the water goes downstream and is used for large hydroelectric dams and irrigation channels to improve agriculture production for affluent people. The government always thinks that, unlike the rich, poor people need only poor solutions.

In this context, we noticed that some villages had very good untapped water sources up in the mountains. It occurred to me that we could use this water to improve livelihoods through electricity access, but at first, I did not know how. I discussed this with my Director who consulted a few technical experts. One person named Jogesh, from Utarakhanda, visited one of our sites and said the site could produce 15 to 25 KW of electricity. Using their feasibility report we decided to construct a micro hydro project. Fortunately, at that time we had an Australian volunteer named Michael who had been working with Gram Vikas for two years, under the leadership of then-Program Manager, Liby Johnson [now Executive Director of Gram Vikas]. Michael provided technical support to initiate the first micro hydro project in a tribal village called Amthaguda in Kalahandi District. When Michael left, Dipti Vaghela [now Network Facilitator and Manager at HPNET] joined Gram Vikas, providing technical support to continue the project and she helped to bring it to completion. We were able to work within a very restrictive budget, since the community contributed in-kind labour and provided local materials free of cost, and we developed a system for monthly tariff collection. We also supported one youth from the village to receive training on system operation and maintenance. This project not only generated electricity, but also helped the community to increase their food production through land irrigation, provided 100% of households with 24/7 access to safe water for toilets, and improved health by mitigating water borne diseases.

The day electricity came to the village, people celebrated by cooking a bhoji for a jatra (as if there was a festival for the whole community). What the government had not accomplished over 60 years, the community accomplished in two years, with perseverance to overcome various challenges. Upon seeing the success of micro hydro in Amthaguda village, other nearby villages stepped forward to develop community hydro as well. To date, five hydro mini-grids are running in Kalahandi District.

Yes, I have encountered many challenges in both my personal life and working life. Firstly, as a woman, it is often not easy to be accepted as a leader; often you are only accepted when there is no alternative and only once you have proven yourself. I first faced this challenge and demonstrated my leadership capacity in Thuamul Rampur project in Kalahandi District.

Thuamul Rampur project was, and remains, one of the key tribal community sites for Gram Vikas. It was situated in a forest reserve area with no communication services and only one pucca (“paved”) road from Bhawanipatna district headquarters to Thuamulpur block headquarters, thus I had to walk part of the journey. Due to its extreme remoteness and underdevelopment, in a hilly area with dense forest, those living in the area faced many challenges including malaria, lack of electricity, no running water, and dangerous wildlife encounters. Moreover, the site was 450 kms from Gram Vikas headquarters. The project was initiated in 1988. From ‘88 to ’94, 6 Team Leaders were posted within 6 years. Most of them were not interested to stay in such poor conditions for extended periods. Not only Team Leaders, but also staff turnover was very high. Those who visited the site and didn’t quit immediately often came down with malaria after a few weeks (although this problem has since reduced). As such, amongst Gram Vikas staff, this project was considered the most difficult. Often, staff would resign before transferring to Thuamul Rampur having heard of its challenging conditions; and those who were successful in Thuamul Rampur earned great respect. The area was rich in natural resources like water sources, forests and minerals, and both a challenging yet inspiring context for outsiders.

In 1995, I was posted as a Team Leader in Thuamul Rampur. I was shocked to find that 95% of my staff were much more senior than myself and there was only one woman out of 45. “Who will take me seriously,” I thought. The staff advised that, being a woman, I should not go to the field and, rather, remain working from the project office. All the community work would be done by them, and I was only to process bills and pay vouchers. I was confused and afraid -- how could I lead the project without doing field work and engaging with communities? I informed them that my primary job required field visits and I acted accordingly. During field visits I noticed some problems including improper reporting of finances and staff work hours, and lack of discipline among staff when in the villages. I tried my best to correct these issues, but it was not an easy task for me. The staff disliked the changes I was trying to instill and created obstacles for me. The situation worsened to the point that my supervisor became my adversary; but thankfully the Gram Vikas Director was able to understand my intentions and was supportive.

During that challenging time in Thuamul Rampur I discussed the situation with our Director and thankfully he provided moral and strategic support, even directly in the field. As a result, I was able to continue and became the only Team Leader who successfully completed 5 years as a Team Leader in Thuamul Rampur. I’m happy to see that the programs initiated during my leadership continue to be sustained by communities, including: establishing the Residential tribal school named Gramvikas Shikhsyaniketan in August, 1998; the Livelihood, Water & Sanitation Programme which has benefitted 100% of the households in the village; solar PV systems and biodiesel projects (biodiesel produced from un-utilized local seeds, in collaboration with a Canadian NGO named CTx Green); water pumping from dug wells to supply bathrooms in tribal villages; and, of course, the micro hydro initiatives.

More broadly, I benefited from maximizing the time I spent with community members, getting to know the reality on the ground, and I learned many new things from them. I always tried to be a friend to community members, not a boss. Acceptance by community members is one of the most important factors for getting work done. Sharing knowledge and, in turn, learning from local knowledge is one of the most important tools. Local peoples’ practical knowledge is more useful than any outsider’s knowledge. For this reason, I succeeded by empowering local people to become leaders who would be the real drivers of successful development programs.

“I succeeded by empowering local people to become leaders who would be the real drivers of successful development programs.”

First and foremost, a Team Leader or Executive Director must have confidence in women team members that they can do good work. An attitudinal change is required.

I overcame obstacles many thanks to my Assistant Director, Mrs. Anthiya Madiath, who motivated me in so many ways and helped me to build my capacity through training, exposure visits, critical meetings, and mentorship. Thanks to her support I decided to commit myself to the empowerment of tribal and marginalized communities work until the end of my life. Training, exposure, and inclusion in decision-making are some key ways that organizations can build the capacity of women practitioners.

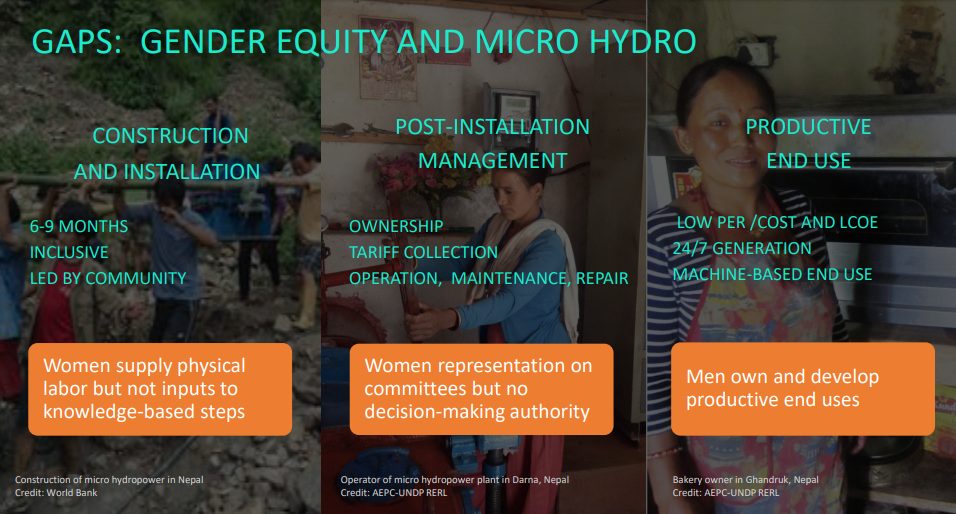

Women and water are inseparable. We cannot think of gender equity and water management separately. In the context where I have lived and worked, it is women’s primary responsibility to get water for the household and it is women who do all work related to water, from agriculture to household labour. If water is mis-utilized the first people who will suffer badly are women. As a result, we’ve found that women are highly motivated to participate in water management initiatives.

“Women and water are inseparable. We cannot think of gender equity and water management separately.”

At the end of my 33-year career with Gram Vikas, when at times I feel that friends and acquaintances may have forgotten my contributions to the organization, I feel touched that the communities I engaged with haven’t forgotten me. Whenever I feel down, very often my spirit is lifted when I receive a phone call from a community member saying, “Didi [meaning elder sister in Oriya], please come to visit our village”.

I feel proud of the many development initiatives that I initiated, which improved the livelihoods of tribal communities. I am lucky that I had the opportunity to work with tribal communities in the remote interior through Gram Vikas, in inaccessible areas where development was once just a dream. Initially, I thought it was impossible to work in such remote areas where you could not manage adequate food and mobility, but thanks to support from colleagues, training, exposure, etc., I could succeed. Overall, I am very thankful to Gram Vikas for a highly rewarding career.

One of my proudest accomplishments came out of one of the most difficult struggles in my career. In 1992, I was posted as Team Leader in Rudhapader project, in Ganjam district. During my field visit I noticed that villagers were cultivating a small patch of brinjal in infertile land within the forest reserve; for this, every year, the forest guard and rangers took bribes from them. I motivated the community to shift to cashew plantations instead of brinjal, which would result in a better return. They agreed and implemented this successfully with financial support from Gram Vikas. The next year, the forest rangers asked for bribes, but I encouraged the community not to pay any bribe to anyone. When they didn’t pay, the rangers became angry. They illegally arrested people and kept them in the Tarasing Rang police station. When it came to my notice I rushed to the station and confronted them. In the end, they released the community members, but 10 forest and criminal cases were filed in my name in 1992. I had to regularly attend court from then until 2004. That 12-year experience is one I will never forget, but at the end of my painful struggle I saw a remarkable outcome.

In total 20 families were living in the village. From 1995/1996 onwards, each family was earning a minimum of 20,000 to 50,000 RP cash in a year from cashew sales (depending on land size). Today, after a long fight, every family in the village has a land record in their name under the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 (FRA). Now the village scenario has completely transformed. Recently a family showed me their new marble house through a video call. Often, they call and invite me to visit their village. I feel very proud of what was accomplished in this village.

Nothing is impossible. Everything is possible with hard work, willingness and honesty. Your struggle today will give you happiness tomorrow that will last the rest of your life.

Finally, I’ll share a quote that I feel is 100% correct when looking back at my experiences: “Love your job but don’t love your company, because you may not know when your company stops loving you” -- Dr. Abdul Kalam, the former President of India. It reminds me that, as a woman leader, being committed to the upliftment of marginalized communities may mean displeasing some people in the process – but the end result, achieving my mission, is worth being steadfast.