| Protel Multi Energy (PME) was incorporated in early 2011 by Mr. Komarudin, an electrical engineer with a strong background in renewable energy, and a passion for small-scale hydropower, cultivated over 15 years. Previously, Mr. Komarudin worked with Entec AG, a Swiss consulting and engineering company specialized in small hydropower. Experienced with worldwide projects in technology transfer, he has provided assistance in developing countries, especially in crossflow turbine (T14/T15) and controller technology. |

|

Public, non-government, and private sector actors each play important roles in the small-scale hydropower landscape. We are often inspired by the tenacity of locally-rooted, private entrepreneurs who are unperturbed by the challenges that come with establishing and running a financially viable business that also serves rural communities. In this guest blog post, we hear from Mr. Komarudin, an entrepreneur who wears many hats as a manufacturer, developer, technical consultant, and micro hydro champion in Bandung, Indonesia. He introduces us to his business, Protel Multi Energy (PME), which has been supporting rural energy access for over a decade. Protel Multi Energy focuses on the manufacturing of affordable Digital Electronic Load Controllers (ELCs), as well as micro hydro and pico hydro turbines (crossflow and Pelton) for rural electrification all over the world. Besides product manufacturing we also assist villagers and project owners in planning and designing micro hydro schemes. Sometimes we offer technical supervision on construction and installation. We are also able to do turnkey projects under certain circumstances. Our ELCs are being used in more than 900 micro hydro sites in 5 continents and more than 30 countries worldwide, with a projected total installed capacity of about 10MW by the end of 2021. Our projects are mostly financed by donors, government agencies or the private sector, as off-grid renewable energy projects for rural development. Nowadays, especially in Indonesia, we are developing many micro hydro projects through Dana Desa (village funds). We often provide support for each stage, starting from site survey, to planning and design, project supervision, supply of equipment and post-installation management. Due to their lack of knowledge and experience, we assist villagers to develop their project as their own responsibility, under our supervision to make sure it runs well with a sustainable approach and reliable equipment. To learn more about PME and access many useful tutorial videos, visit our YouTube channel!

0 Comments

We are glad to have HPNET member Mr. Takum Chang from the Nagaland Empowerment of People Through Energy Development (NEPeD) share about NEPeD’s pico hydro approach.  Credit: http://surveying-mapping-gis.blogspot.com/ Credit: http://surveying-mapping-gis.blogspot.com/ Introduction Nagaland is one of the seven sister states of northeast India. The region is rich in biodiversity and natural resources. There are many villages in Nagaland that have access to small rivers and streams. These rivers have enough hydro power potential to meet the electricity demand of the entire state. Since 2007, NEPeD’s mission has been to educate and empower people to help maintain biodiversity and vital ecosystem services, while simultaneously ensuring equitable access to adequate clean energy supply. NEPeD manufacturers and installs pico hydro systems called Hydrogers, a term coined by NEPeD, joining the words hydro and generator. It refers to the type of pico hydro system developed by NEPeD. Clean and green energy through NEPeD’s efforts, however small, could contribute to the mitigation of global climate change concerns in the Eastern Himalayan region as it de-couples the dependence on traditional fossil fuels.  “Made-in-Nagaland” Hydroger for pico hydro developed by NEPeD. Credit: NEPeD “Made-in-Nagaland” Hydroger for pico hydro developed by NEPeD. Credit: NEPeD Local Technology Development The most interesting aspect about Hydroger Systems is that they are not imported from elsewhere but are indigenously manufactured in Nagaland itself. NEPeD established the Centre of Excellence for Renewable Energy Studies (CERES) to manufacture hydro technology locally, making it available easily in the region. NEPeD, in collaboration with the Nagaland Tool Room and Training Centre (NTTC), Dimapur, ventured into the indigenization of the Hydroger system. The first funding towards mass production of Hydroger was supported by National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) under Rural Innovation Fund (RIF). The Hydroger model manufactured in CERES has been successfully tested and certified at the Alternate Hydro Energy Centre (AHEC) at Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Roorkee. CERES is the only known centre to solely focus on mass production of Hydroger technology. CERES is also the hub of knowledge dissemination. Many trainings were provided to small hydro engineers, technicians and practitioners in the region. NEPeD is also supporting a private entrepreneur under its entrepreneurship development programme for research and development of the Electronic Load Controller (ELC). Local Capacity Building To maintain the Hydroger Project’s sustainability and continuity of efforts in the long run, it is key to have a cadre of skilled rural engineers on-site. NEPeD has trained more than 50 engineers to oversee and manage the sites’ operation. NEPeD has also prepared them to help up-scale the Hydroger installation in the future. They will provide hands-on support, ranging from site selection, maintenance, to installation of higher capacity modules. Employing rural engineers and technicians will not only help to generate income but also to grow the rural economy.  Community training on pico hydro and watershed management. Credit: NEPeD Community training on pico hydro and watershed management. Credit: NEPeD Socio-Environmental Governance There are many dimensions to the Hydroger Project. Not only does it help to address basic electricity needs of people living in the villages, but it also has impacts on the environment, social and economic sectors. Most of the NEPeD’s Hydroger installations are owned and managed by the communities. Communities with Hydroger systems undergo capacity building and conservation of environmental ideas is deeply ingrained as part of this training. Each project site is also capacitated and facilitated to evolve their own revenue model. Hydroger being a clean and alternative source of renewable energy has made an impact through energy delivery. NEPeD while introducing and promoting this technology, has also encouraged the villagers to maintain the upland catchment areas to ensure a sustainable supply of water. Targeted Impact Setting up of Hydroger projects have been done following a model that is holistic and integrated. It is designed to be easily replicated. The common sectoral impacts as registered by the existing Hydroger Project sites are as listed below. Social - Community ownership - Revitalized social dynamics-greater community bonding and interaction - Health sanitation related impacts - Empowerment and involvement of women in the decision-making process Economic - Source of revenue generation for the community - Employment of individuals - Increased man hours industries such as handicrafts Environment - Generation of clean sustainable energy - Decreased dependence on fossil fuels - Spreading/ creating awareness on environmental fronts - Community commitments to conserve and protect catchment areas and biodiversity Replication across NE India The benefits have also been appraised by the neighbouring States that want to replicate this model. The low cost, light weight, accessible operation and versatile utility of the Hydroger systems have allowed widespread adoption. Besides Nagaland, the Hydroger is used in Meghalaya, Sikkim, Manipur, Arunachal Pradesh, Maharashtra and Jammu & Kashmir. NEPeD has has installed over 50 units across northeast India, mostly in Nagaland. Another 50+ units will be installed in partnership with the Meghalaya Basin Development Authority, where NEPeD will also train technicians in each village to install, manage, and troubleshoot. There has also been an interest to develop Hydrogers commercially. Next Phase Vision The Hydroger Project has successfully evolved into a model for a sustainable and community-owned electricity generation in rural areas. It is improving their quality of life, improving their livelihoods, creating unprecedented awareness, community participation, and most importantly developing governance at a decentralized level. The initiative is based on the realization that the availability of energy is vital for sustainable development and poverty reduction efforts. Energy affects various aspects of development - social, economic, and environmental - including livelihoods, access to water, agricultural productivity, health, population levels, education, and gender-related issues. NEPED also seeks to further develop state level capacity to manage the environment and natural resources; integrate environmental and energy dimensions into poverty reduction strategies and state level development frameworks; and strengthen the role of communities and of women in promoting sustainable development. At the same time, NEPED understands that sustainable energy security initiatives have multiple dimensions. By focusing on micro/mini hydropower as a reliable renewable source for providing energy security in a difficult terrain where grid connectivity is available erratically, NEPED also intends to create replicable models for watersheds in Nagaland, other North-eastern states, and the Himalayan sub-region.  Hydro resource in eastern Nagaland. Credit: NEPeD Hydro resource in eastern Nagaland. Credit: NEPeD Recommendations 1. Transition from pico to micro hydro Over the years, the energy demand of rural communities has increased. They require reliable, uninterrupted, and sufficient energy supply. They require higher capacity than the current 3kW Hydrogers produce. Although some villages have access to the central grid, electricity from the Hydroger is more cost effective then the central grid. Therefore communities have been demanding Hydrogers of higher capacity. Farmers have expressed the need for energy to add value to their agricultural processing. NEPeD will strive to leverage the resources for installing higher capacity hydro power systems and hopes to achieve its objective to integrate the environmental and energy dimensions into rural economic development strategies. NEPeD’s aim to transition from pico to micro hydro systems is a natural progression given the large energy demand-supply gap in Nagaland. 2. Access to subsidy and credit For NEPeD and also for many other small hydro practitioners in North East India, the only source of funding is the Ministry under Government of India (GOI). However, most of the funding from the Ministry must go through its state-level nodal agencies. It is not easy for other departments or practitioners to access funding from the Ministry. To address this challenge, special consideration or arrangement of funding processes for other departments and practitioners will accelerate prospects of small hydro systems. Private practitioners and implementers have to be encouraged, especially in Nagaland, to pick up the pace for development of small hydro in the state. Credit facilities from banks and other financial institutions could be another option for the communities to get resources for setting up small hydro systems of capacity as per their total energy requirement and also meeting the energy requirement for productive use. The 10 poorest provinces of the Philippines are located on the island of Mindanao. As with other marginalized places in our world -- where rural, indigenous populations face social exclusion, frustration, and hopelessness in the face of extractive and inequitable economic and political systems -- portions of the island are controlled by separatist movements, with innocent indigenous communities caught in the crossfire between the government and the rebels. The situation exacerbates efforts to bring infrastructure for basic needs (e.g. potable water and electricity) and magnifies the innate challenges of rural development work in developing contexts. In March 1993, a small, young, and local group of alternative development professionals came together with the mission to improve the socio-cultural, economic, and environmental well-being in rural Mindanao, by promoting the sustainable utilization and management of appropriate renewable energy sources and other natural resources. Versed in technical, ecological, and social aspects of sustainable rural development, the group was called Yamog, translating as dew drops in the Cebuano language. Distinct from the conventional community development approaches at the time, the pioneers of the Yamog Renewable Energy Development Group, Inc., pursued a path that was anchored on renewable energy as a springboard towards positive, meaningful and enduring change at the grassroots level, to end decades of deprivation. It pioneered utilizing renewable energy, not only to lessen the dependence of poor communities on fossil fuels, but also to offer it as a vehicle for marginalized communities to become sustainable. When Yamog was established 20-years ago, nearly half of Mindanao was un-electrified. Even now Mindinao's largest city faces daily blackouts lasting 12 hours. Yet, the nearly 2500 households that have electrified their villages with Yamog's help do not have to rely on the central grid and can access 24/7 electricity. Yamog continues to facilitate other communities in rural Mindanao and Visayas in generating their own electricity from micro hydro or solar power. The effectiveness of Yamog's work is rooted its integrated approach to community-based micro hydropower. In each project, Yamog's long-experienced staff of 7 are committed to instilling the environmental, institutional, social, and technical aspects that are critical to the project's life. Watershed protection and strengthening Because the output of any micro hydropower unit is dependent on the stream flow, Yamog's implementation process starts with a focus on rehabilitating the source of the stream -- the watershed. Yamog works closely with the community to evaluate, protect, and strengthen the watershed of the proposed micro hydro site. After signs of a robust watershed and the community's will to preserve it emerge, Yamog moves onto installing the micro hydro hardware. The process can add an extra year to the project implementation, often with additional communities to facilitate (e.g. where the upstream community managing the watershed is km's away from the micro hydro community downstream). Yet, with increasing climate change impacting not only micro hydro but also the community's access to drinking and irrigation water, prioritizing resilient watersheds is well worth the added effort and time.

Meeting with Yamog, the Mayor, and HPNET Coordinator. Photo Credit: Yamog Meeting with Yamog, the Mayor, and HPNET Coordinator. Photo Credit: Yamog Involvement of local government A key aspect to Yamog's work is facilitating communities to generate support from the leaders of their barangay (the most local administrative unit) for watershed strengthening and micro hydropower implementation. Although challenging, this process has resulted in community hydropower units that have greater vested stake from the local government, and a paved path for the community to reach out to local officials regarding other village development needs. Support from local government can also help establish productive use for community income generation from micro hydropower, e.g. financing of agro processing units such oil mills and rice hullers. Community governance of the technology In parallel to watershed strengthening and micro hydro installation, Yamog facilitates the community to identify its governing strengths and build upon them, in order to develop a unified governance of the new micro hydropower unit. Yamog staff build the capacity of community leaders to manage and lead project implementation from its start. At various stages Yamog holds in-depth technical and institutional training for community members. This has ensured that by the time of commissioning electricity generation, the community's governance structure can independently manage the electricity tariff collection, community fund, technical operation, maintenance, and productive use of the micro hydro system. Local network of technical experts Since Yamog does not fabricate its own turbines and load controllers, it ensures that the hardware developers commit to delivering high quality systems and local training to community-level technicians. Having implement nearly 30 projects, Yamog has developed a village-to-village network of technical experts for civil works installation and trouble shooting of electro-mechanical components. For example, the village masons from completed projects mentor the masons of new projects, carrying forward technical lessons of earlier projects. This in-turn has led to a local knowledge sharing network that can sustain itself without the involvement of Yamog. In addition, it has helped to diversify the skillsets in indigenous communities, where traditional livelihoods are at risk due to extractive activities of mainstream development.

With a small team, instead of quantity of projects Yamog's work has focused on process and quality to ensure long-term sustainability. Every year the team typically commits to 1-2 projects and implements them with utmost care, focusing on the elements explained above. While larger organizations, with greater number of staff and funding, can easily implement many projects in parallel, they can be prone to frequent staff turnover and prioritizing targets over processes. In some cases this has led to micro hydropower units that are not long-sustained and soon need rehabilitation. In this context, HPNET takes inspiration from Yamog's steady and process-focused momentum to establish community micro hydropower. To give you a glimpse of the Yamog's work in action, below is a brief case study of Lubo village's micro hydropower project.  Micro hydro powerhouse. Photo Credit: D. Vaghela Micro hydro powerhouse. Photo Credit: D. Vaghela Case Study: Sustainability of Lubo Micro Hydro Project -- Two Years Later The residents of Sitio Lubo continue to enjoy the benefits of having a 35-kilowatt micro-hydropower system. Since the renewable energy project was handed-over by Yamog to the Lubo Renewable Energy Community Association (LURECDA) in June 2013, the lives of the people in this isolated and marginalized community have steadily changed for the better. Situated deep in the highlands of Barangay Ned, Lake Sebu in the province of South Cotabato, Sitio Lubo is an off-grid community inhabited by mostly Christian peasant settlers. It is about 65 kilometers from Koronadal City, South Cotabato. It is populated by 150 households who, for many decades, have been resigned to their dismal fate of being deprived of opportunities that would improve their socio-economic situation. No one among them could have imagined that their vast water resource would someday lift them up from their collective sense of hopelessness and helplessness.  Yamog team with micro hydro community leaders. Photo Credit: D. Vaghela Yamog team with micro hydro community leaders. Photo Credit: D. Vaghela At present, 127 households and selected strategic locations of the community are now brightly illuminated at night by energy-saving bulbs. In effect, the 35-kilowatt water-driven renewable energy system has freed the residents of Lubo from decades of heavy dependence on kerosene as the main form of household lighting at night, and as a major source of energy for other community and household activities. Moreover, about 20 households have engaged in small income generating activities after having procured refrigerators to store locally-made food products (which are kept fresh because of the presence of 24-hour electricity) for sale. Taking advantage of the presence of electricity, both men and women can also engage in income generating activities even at night. Schoolchildren are inspired to work on their nightly home works because of the presence of good lighting within their households. Gone were the days when they had to contend with the unsteady illumination from kerosene lamps which spewed a lot of carbon dioxide that endangered their health.

Two public schools with a total of 560 students are also now enjoying the comfort of having unhampered electricity during classes. For the first time, these students are now able to use computers for learning, while teachers can now also use computers to prepare lesson plans, learning aids, aptitude tests, and reports. Places for important social gatherings that utilize electricity for lighting and sound systems, like the Sitio Hall and local churches, are abuzz with activities.

Yamog micro hydro training. Photo Credit: Yamog Yamog micro hydro training. Photo Credit: Yamog Early in the course of project implementation three years ago, Yamog invested a lot of effort in addressing the software component – that is social infrastructure building – a very crucial element for project sustainability. Capacity building activities in the field of technical operation and maintenance, financial management, organizational building and strengthening, and watershed management, have been conducted in order for the project beneficiaries to acquire the required knowledge, attitudes and skills that would improve their chances of effectively managing their micro-hydro system over the long term. Now it appears that all those efforts have generated very encouraging results as evidenced by the following:

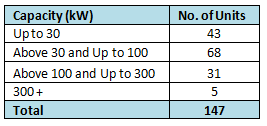

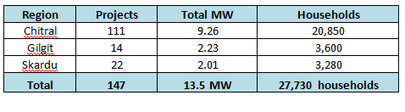

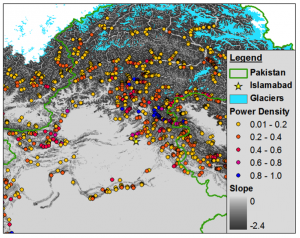

Next generation of Sitio Lubo. Photo Credit: Yamog Next generation of Sitio Lubo. Photo Credit: Yamog Brimming with enthusiasm, the residents of Sitio Lubo are looking forward to the coming years with a list of more things to do. After two years of operating and maintaining their micro-hydropower system, plans of utilizing the almost unlimited supply of energy at daytime are afoot. Next in the drawing board are the construction of a corn mill, hammer mill (to produce feed stocks using organic raw materials for hog-raising), coffee huller, and other productive end uses of their MHP electricity. All these are aimed at raising family incomes. Fundraising for these spin-off projects would be a big challenge, but they are optimistic that they would achieve these additional facilities that they are aspiring for in the next two years. At the United Nations SE4ALL Forum in May 2015 there was much good discussion on mini-grids. Anytime the mini-grid technology was specified, it was assumed to be solar PV. However, there are other -- unsung but proven mini-grid technologies that have long provided electricity -- such as micro hydropower, biomass gassifiers, and small-scale wind. Needless to say, during the four-day event attended by 2000 persons and a multitude of speakers, we were ecstatic to hear at least one member of a high-level panel highlight micro hydropower! The panelist was from the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), working across 30 countries on an array of sustainable development projects.  Northern Pakistan mountains. Photo: Ashden Awards Northern Pakistan mountains. Photo: Ashden Awards AKDN's evolution began with the Aga Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP) established in 1982. Since then, AKRSP has been committed to the remotest (and likely some of the most beautiful) high altitude regions -- the Northwest Frontier (Chitral) and Baltistan -- where living conditions are harsh and communities are resilient. AKRSP has blazed trails in this region, literally. With ample glacial melt waters in the region and little electrification, community micro hydropower became a flagship of AKRSP's multi-faceted, participatory rural development approach, focusing on social, economic, and institutional development. AKRSP's approach and achievements have justifiably won the prestigious Ashden Award and the Global Development Network's Japanese Award for Most Innovative Development Project.  Micro hydro project civil works structure and penstock. Photo: AKRSP Micro hydro project civil works structure and penstock. Photo: AKRSP Scalability using a Participatory, Iterative Approach AKRSP's guiding philosophy has been that marginalized communities have an innate potential to manage their own development. In fact, AKRSP was the first to facilitate community-owned and managed infrastructure in Pakistan, including micro hydropower, irrigation channels, and roads. In its earliest projects, AKRSP observed the gap between public sector services and village households. Thereof, at the core its approach has been the development of village-level organizations (VOs) that are capable of interfacing with local government agencies. As AKRSP's lead Miraj Khan writes, "VO's, when informed and empowered, can negotiate and better bargain for these [public] services on behalf of their members, than otherwise fragmented and powerless rural societies." Khan attributes its achievement of nearly 200 community-based micro and mini hydropower projects to community organizations. He also attributes the scaled success to a "living design" and "learning by doing" between AKRSP and the communities, where the program was iteratively improved based on the lessons of each project. When AKRSP's model proved its success at scale, it was not long until mainstream development actors requested AKRSP's support to replicate the model. For example, the Sarhad Rural Support Programme (SRSP), also an Ashden awardee, came into being when USAID and the Pakistan government partnered with AKRSP. Such replication has further scaled up AKRSP's model, with VO's still at its foundation.  Micro hydro stream in northern Pakistan village. Photo: Ashden Awards Micro hydro stream in northern Pakistan village. Photo: Ashden Awards Leveraging the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) While the United Nations Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) is one way for community-based decentralized renewable energy (DRE) projects to become financially viable, in practice few DRE developers have been able to meet the complex application requirements and the institutional bundling of smaller, kilowatt projects into substantial megawatts. In 2009, AKRSP became one of the few to successfully leverage CDM using a community-based approach, initiating a 7-year program involving 90 micro hydropower projects with a total capacity of 15 MW for rural electrification. The program, costing USD 17.42 million, has started to build AKRSP'S Community Development Carbon Fund, approved under the CDM efforts of Pakistan. For this AKRSP has an Emission Reduction Purchase Agreement (ERPA) with the World Bank. The CDM project will generate an estimated 612,342 tCO2eq (ton carbon dioxide equivalent) of Certified Emission Reductions (CERs) in the first 7-year crediting period, with the option of renewing for two additional 7-year periods. As of now, 42 projects are in operation and 10 have been commissioned this year, all generating CERs. For the remaining 38 projects, AKRSP is seeking support for capital costs. Further details on the program can be found here.  Productive use of electricity. Photo: AKRSP Productive use of electricity. Photo: AKRSP From Micro to Mini-Grids Based on the overall progress of micro and mini hydropower in Pakistan, AKRSP has observed that most of the investment in the sector, particularly for the peripheral villages, focuses only on power generation, without addressing the issues of diversified demand of downstream users that has resulted from the change in economic conditions. AKRSP's sees great opportunity in linking increased power generation with economic and commercial activities in the main load centers for creating greater socio-economic development of the area. The productive use of energy by communities, with special focus on enterprise and income generating activities, will lead to the rapid growth of the local economy. To address this, AKRSP has concluded that although scattered and small villages with sufficient water flow and feasible sites naturally provide an easy option to construct a small unit for each village, in some villages the power generation is merely enough for lighting purpose. Yet in other villages, due to availability of more water, the units generate more power than needed. This situation has pushed AKRSP to think about developing a new system for improved power management and more productive use of energy created by micro hydro project with varied capacities. AKRSP’s new hydro development strategy entails increasing power output (capacities and efficiency) and connecting multiple small units for stable supply of electricity into a mini-grid, thereby creating greater economic opportunities by using micro hydropower. Similar efforts have been initiated in Indonesia, Myanmar, and Nepal. This video from Nepal explains technical aspects.  Micro hydro project silting tank. Photo: AKRSP Micro hydro project silting tank. Photo: AKRSP AKRSP estimates that 2.3 MW of micro hydropower can be transformed from micro to mini-grids, benefiting 24 villages in two valleys of northern Pakistan. AKRSP has recently installed two mini hydropower units, of 500 kW and 800 kW, in Laspur and Yarkhun valleys of Chitral District, along with establishing two local utility companies for the operation and maintenance of these systems. AKRSP will conduct a feasibility study for connecting these units into a mini-grid that can provide power to more communities. The Laspur and Yarkhun valleys also include smaller mini-hydro units, ranging from 100-300 kW, where feasibility studies are being conducted for both mini-grids and grid inter-connectivity. Other HPNET members have identified grid inter-connectivity and inter-linking multiple micro hydropower projects into mini-grids as prime priorities for sustaining the work of local practitioners. Local developers fuel local economies and provide better post-installation operation and maintenance services. HPNET looks very forward to learning from AKRSP's vision and firsthand experience to connect micro hydropower units at the sub-valley level, then at the valley, and finally with the national grid. While this is a common sense goal, most governments and international donors in the region are not familiar enough with its significance, especially as a viable alternative to destructive and inequitable, central-grid based power sources, such as coal and large hydropower, for rural electrification. No doubt, in time, AKRSP will prove the viability of its vision for interconnected micro hydropower mini-grids, and HPNET will be ready to assist in transferring its know how to the region. More information and research on AKRSP's work can be found here. By Nauman Amin and Dipti Vaghela In the realm of integrated approaches to community-based micro hydro, we take inspiration from SIBAT, a country-wide Filipino network and people's organization advancing community-based renewable energy applications, sustainable agriculture techniques, and water access solutions. Organization Evolution SIBAT's Filipino name, Sibol Ng Agham At Teknolohiya, translates as a wellspring of science and technology. In 1984, several non-government organizations, including science and technology leaders of the country, synergized to help alleviate the struggles of rural communities with the use of appropriate technology The endeavor established SIBAT as a network to coordinate capacity building for organizations that develop technology for rural areas. Over the next decade SIBAT led the country's movement for sustainable agriculture, in empowering communities to return to organic farming with improved techniques. In 1994, SIBAT began capacity building work on rural energy and water solutions. Achievements With a relatively small staff (~25 persons), SIBAT's achievements have been impressive:

Challenges With 30 years of commitment to rural communities, SIBAT's work faces the following challenges and opportunities: Practice-to-policy In the late 90’s and onward, SIBAT joined efforts for policy development on sustainable agriculture. It participated in the crafting of the Implementing Rules and Regulations of the Organic Agriculture Law which took effect in 2012. While the law is in place, it lacks mechanisms to strengthen the small-scale, organic farmer. SIBAT faces a similar uphill in reforming the country's renewable energy law, so that small and community-based power producers are part of the national strategy. To scale community-based energy projects, SIBAT seeks to change the current Renewable Energy policy. Towards this goal, it has taken the lead in facilitating partnerships and exchange events among practice, policy, advocacy, and academic stakeholders. Rehabilitating from typhoon-damage

With increasing climate change, devastating typhoons frequent the Philippines, particularly SIBAT's focus regions. While funding for new projects comes easily, support for rehabilitating already commissioned projects is a challenge. SIBAT is working to better document the need for and approach to rehabilitating CBRES projects, by reaching out to appropriate donors and finding ways to work within each community's financial strengths. Want to be Involved? Over the years, SIBAT has nurtured many visiting volunteers to firsthand learn from rural communities and make meaningful contributions. SIBAT continues to accept volunteers. Details can be found here. By HPNET members Victoria Lopez, Shen Maglinte, and Dipti Vaghela |

Categories

All

Archives

February 2023

|