In this edition, we spoke with Tri Mumpuni, the Executive Director of IBEKA (Institut Bisnis dan Ekonomi Kerakyatan), who has been engaged in rural development work in Indonesia for more than 30 years. Together with her husband and her team, they have implemented more than 60 micro hydro and pico hydro projects across the archipelago. For her dedication, she has won various international awards, including WWF Climate Hero in 2005, Ashden Awards 2012, and ASEAN Social Impact Award in 2018.

Tri Mumpuni, also known as Ibu Puni, shared with us her journey as a female micro hydro practitioner in Indonesia and her work to prepare the next generation in micro hydro and social development sectors.

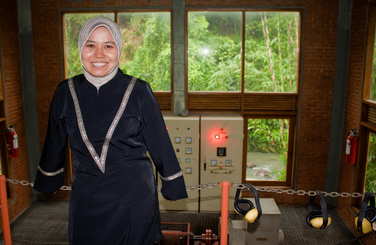

Tri Mumpuni at Cinta Mekar MHP. Credit: T.Mumpuni

Tri Mumpuni at Cinta Mekar MHP. Credit: T.Mumpuni I started in 1996. My husband, Pak Iskandar, started way earlier. He is an engineer and he has the expertise in micro hydro technology.

We work together as a team. He focuses on technical aspects, and I focus on the social aspects.

For a long time, people who live in the remote areas have been relying on diesel gensets or as a quick solution when they need electricity. Unfortunately, this is not stable nor sustainable. It brings profit to some people, but we can’t rely on it in the long run. That’s what we’re trying to change. But first, what we need is to change the people’s mindset.

Statistically, the electrification ratio in Indonesia is high (99%). How is the reality in the villages?

There is a misunderstanding in the definition of electrification ratio. The electrification ratio that has been used in the statistics counts by the number of villages or sub-district, not by inhabitants. So if there is one house in a sub-district that has electricity, it is counted that the whole sub-district is electrified.

This electrification ratio does not factor in the quality of the electricity itself. Based on my observation, there are many villages in Indonesia that only have electricity only from 6 to 10 pm. For example, in Aceh, Kalimantan, and Molucca Island. Ideally, if we are talking about electricity, then it should be available for 24 hours.

I find rural areas in Indonesia have a lot of economic potential. Unfortunately, the lack of energy access has become one of the biggest challenges in rural economic development.

‘Energizing villages’ in literal sense means to enable access to energy, more specifically electricity. However, that is not enough. To develop the economy, we also need humanitarian energy.

To do all these, we need somebody who has concerns, passion, and a genuine heart to think of how to allow this energy to flow to the villages in need. Somebody who could bring ‘light’ as in electricity, but also somebody who can ‘enlighten’ the people and the communities in the villages with the know-how to to develop their economy.

You have to be brave and courageous to bring such a change. How do you play your role here?

It’s God’s calling. I never dreamt of working in the micro hydro sector.

My husband is a micro hydro technology expert, but he cannot do everything alone. When we go to the field, I help him to engage with the local community. We face numerous bureaucratic/ administrative hurdles, and in some areas we have to deal with rackets (preman).

It’s not an easy task. We are doing this for the local people, but we also face challenges imposed directly or indirectly by them. The local values of gotong royong (collective action) have vanished due to corruption in different layers of the government - which does not only hinder our projects, even worse, it hinders rural economic development.

You have been involved in more than 80 micro hydro projects in Indonesia, from Aceh to Papua. What other realities do you see in your MHP journey?

There is one experience that struck me the most. It was in Aceh. Around 20 km from where we worked, we found somebody doing another micro hydro installation but it was badly engineered, had a very poor civil construction. It didn’t function and didn’t serve its purpose.

This is the result of a project that was handled by people who are not experts in MHP. This thing happened because the government used a public tender system for MHP projects, and the company that won this tender, subcontracted the work to several other companies. In the end, the project didn’t meet the quality standard and didn’t benefit the local community.

Who are the people in your team? Are there women who support you on this?

I have a very solid team at IBEKA who are young and well-trained. We also have a woman who is a gender-expert in our team.

Women’s participation in micro hydro remains limited. Generally, women are not yet involved in project initiation or development. The interest in this is still low.

They are more involved in the energy utilization aspect. In Sumba for example, we work closely with women who have a home industry.

How do you ensure the sustainability of your MHP projects?

What I do with the IBEKA team is community-based development. Before we construct anything, we firstly prepare the local communities. For 3 months up to 1 year, we teach them the basic knowledge of MHP, and then we train them to operate and to maintain it so that they can be self-sufficient. This is what we call people-driven development.

We are in close touch with the communities that we are working with. Technology makes it easy now for us to communicate by text/ Whatsapp. We also regularly hold review meetings online.

What does it take for you to become the person who brings this ‘light’ to the people in the rural area?

First of all, I am passionate about what I’m doing, and that is important. In my role, apart from convincing myself, I have to convince others. I am highly committed to my work, and I really hope that there will be regeneration. This is the legacy that I’d like to leave to the younger generation.

What keeps you motivated?

This journey makes me addicted. I cannot stop doing good for others. When we were in the field, completed our construction, and switched on the energy supply for the first time in one evening; people screamed happily and some even sobbed. This happy energy motivates me to keep doing this and go further.

What message would you like to share to readers especially for the next generation of women micro hydro champions?

For us who work in community development, we need to create a driver, not an enabler. I’ll use a mountain bike as an illustration. A person can go to the top of the mountain by biking. Without a bike, this person can still go to the mountain by hiking.

This is how I picture driver and enabler. Micro hydro is a tool for human empowerment, it is not a tool for creating profit. If we do well, profit will follow, but it also has to make a social impact.