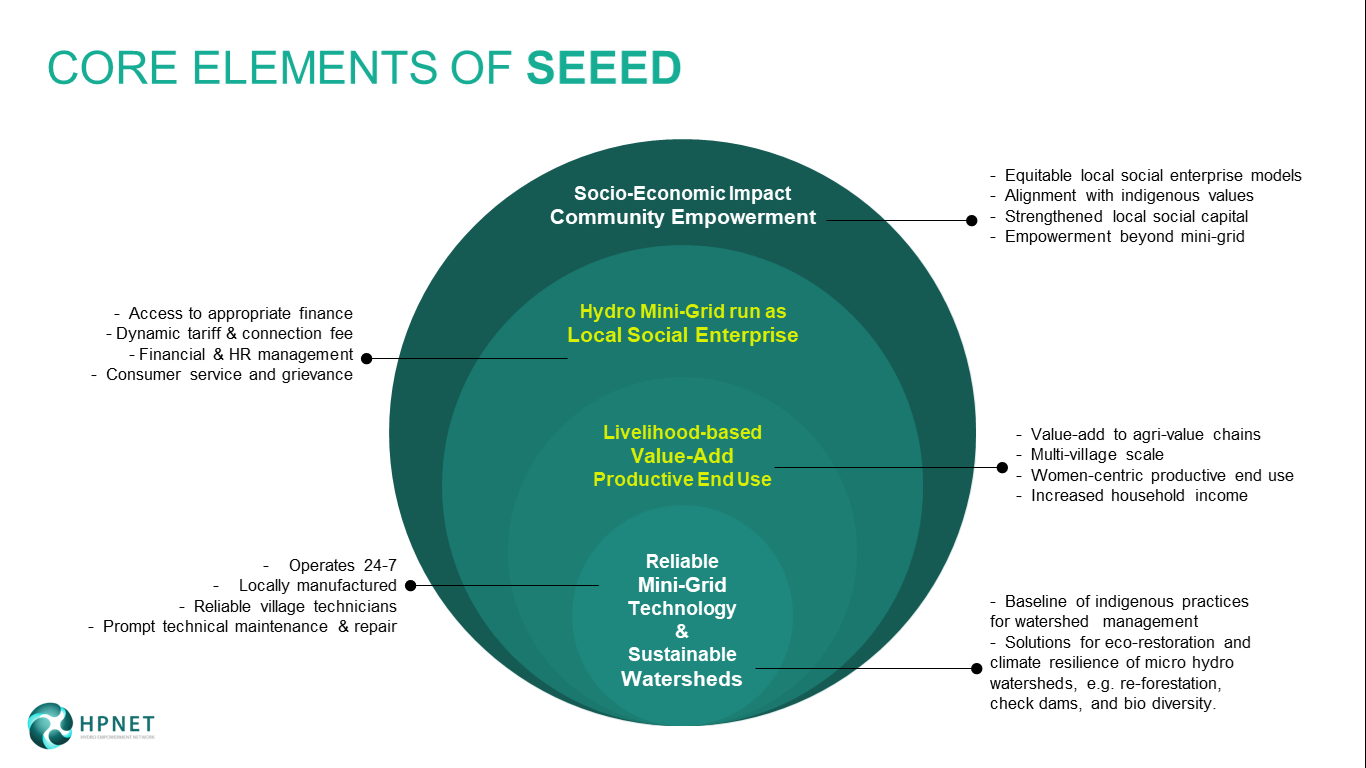

This quarter we spotlight the SEEED elements that can be achieved once reliability is established, namely productive end use and inclusive enterprise aspects that bring value-add to local livelihoods.

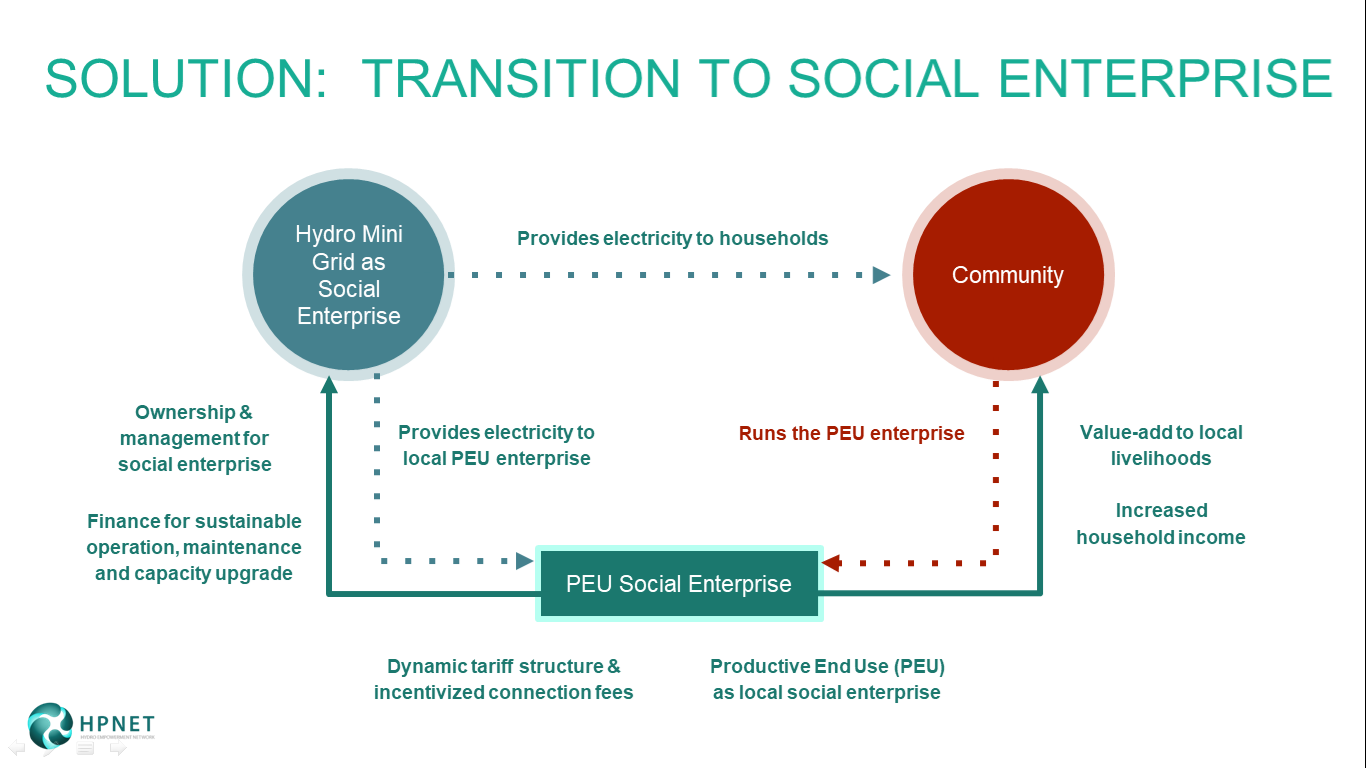

Our initial assessment of hydro mini-grids in the Asia Pacific have identified sub-elements that differentiate various models of inclusive enterprise, including the following:

- Inclusive ownership models

- Cost-recovery models

- Revenue generation models (i.e. connection fees and tariff)

- Effective management processes

- Access to credit and smart subsidy

Asia Pacific

- Winrock Nepal economically revived five micro hydro projects in Nepal, using a peer-to-peer approach, supported by WISIONS. Read more here.

- The association Hydropower for Community Empowerment in Myanmar (HyCEM) is transitioning to cooperative-based models for hydro mini-grids. Read more here.

- Hydropower Concern Ltd., under the leadership of Bir Bahadur Ghale in Nepal, uses a developer-owned approach that has led to high productive end use and economic resilience. Read more here.

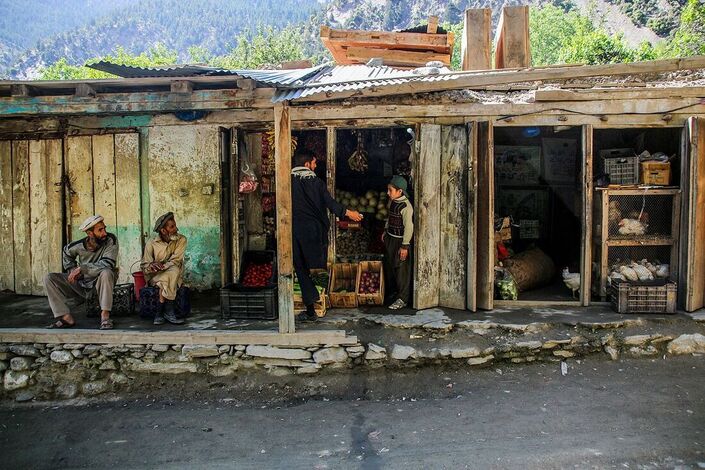

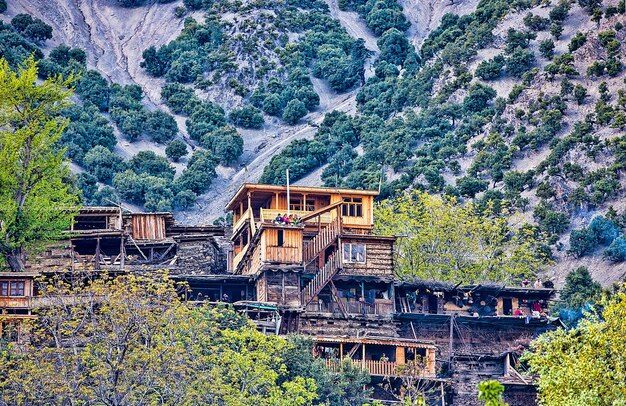

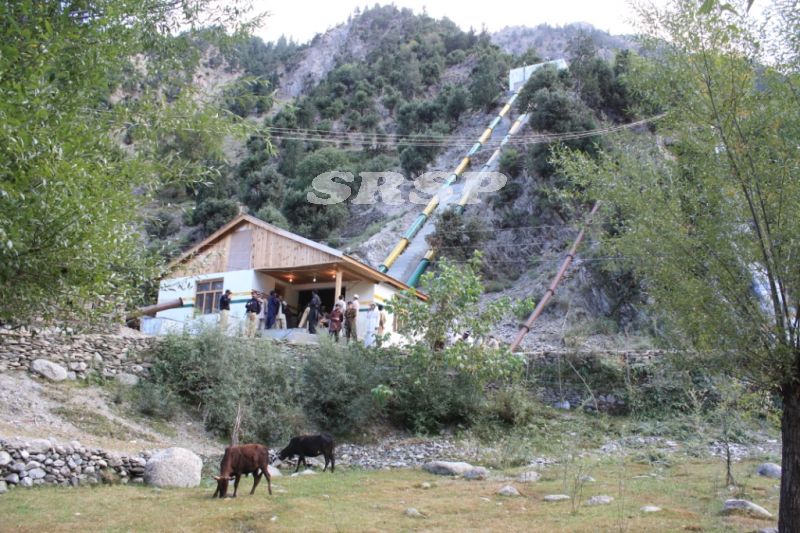

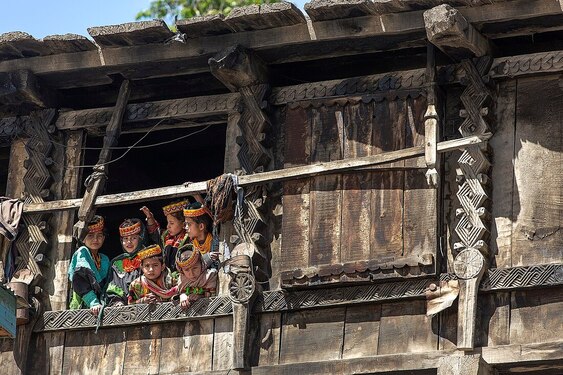

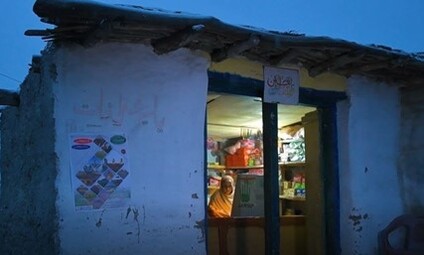

- The Aga Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP) has established community-owned mini-hydropower utilities that are electrifying entire valleys, while nurturing women-led enterprise. Read more here.

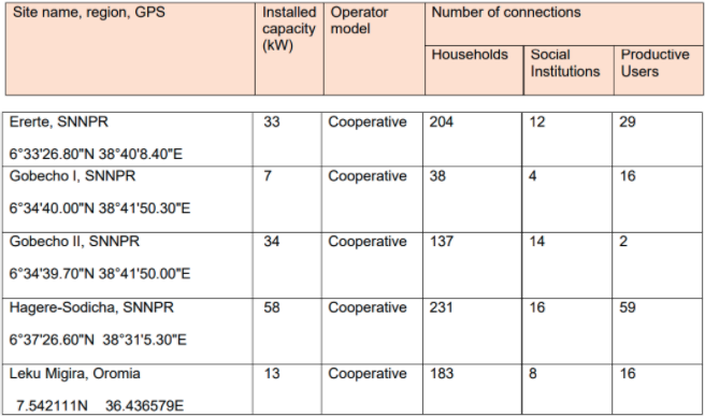

Africa

- Energising Development (EnDev) Ethiopia is initiating a process to revive micro hydro projects, in order to instill optimization in end use and long-term sustainability using an enterprise-based approach. Read more here.

- The Association des Ingénieurs pour le Développement des Energies Renouvelables (AIDER) installs and operates micro hydro systems in Madagascar. Read more here.

Latin America

- Association of Rural Development Workers—Benjamin Linder (ATDER-BL) has interconnected multiple hydro mini-grids with each other, providing electricity to a sub-region in northern Nicaragua. Read more here.

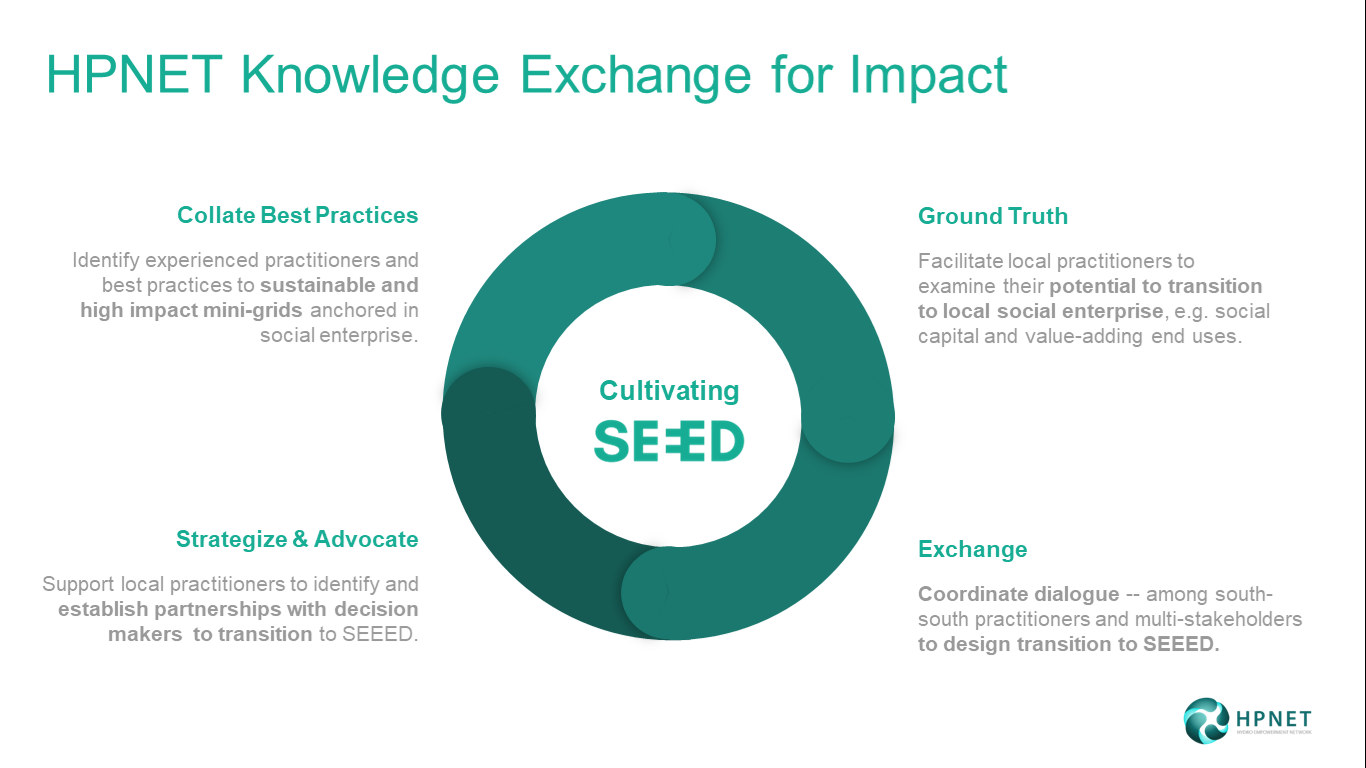

As a part of our knowledge exchange process (below), we continue to look for additional examples for peer-to-peer exchange, in order to collectively advance community-scale hydropower. If you would like to share about your approach to sustainable hydro mini-grids, please let us know here!