Watershed being rehabilitated in Odisha, India. Credit: Gram Vikas.

Watershed being rehabilitated in Odisha, India. Credit: Gram Vikas. In this regard, micro hydro is truly a nature-based solution. Healthy forested watersheds result in sustainable micro hydro systems, where the flow is consistent throughout the year and also resilient to climate change. In addition, healthy forests also help to control erosion during monsoon seasons, which can negatively impact both the micro hydro system and the community. Further, vibrant forests lend themselves to enhanced rural livelihoods, which in turn can benefit from access to electricity, e.g. local processing of agri-forest products.

Because of these linkages, we are connecting micro hydro practitioners to watershed experts. Our network is fortunate to have a few members that focus on both. Gram Vikas, based in Odisha, India, is one such organization.

In fact, the focus on watershed restoration goes beyond micro hydropower for Gram Vikas. Its flagship and award-winning water and sanitation program for rural and marginalized communities strongly highlights practices for watershed (ridge to valley) and springshed (valley to valley) strengthening.

One of the several solutions in this area that Gram Vikas is pioneering is recharging springs. Read on to learn more! For additional articles on watersheds and micro hydro, please see here.

SPRINGS: NATURE'S BOUNTY FOR WATER SECURITY

Mountain Springs are the main water source for most of the tribal population living in the Eastern Ghats range of Odisha. Many of the villages, in the region, are over the hilltops, in the form of scattered hamlets. They get little or no access to streams flowing down to the valleys. About 60% of the population in these hamlets depend upon spring water for basic needs like drinking, domestic use, and for agriculture and livestock. Despite their significance, springs are drying up due to variations in rainfall patterns, changes in land use and reduction in forest cover. Many have become seasonal with low discharge. There are also apparent changes in the quality of water available. Only about 30% of the water sources are estimated to be functioning without any apparent decrease in water availability.

The Springs Initiative aims to develop community-led efforts for springshed management, spring rejuvenation and establishment of water systems by harnessing the potential of perennial springs sustainably. The Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India and UNDP India support the initiative. Gram Vikas took up the initiative, in partnership with village communities and with technical support from ACWADAM, in selected blocks of Gajapati, Kandhamal and Kalahandi districts of Odisha.

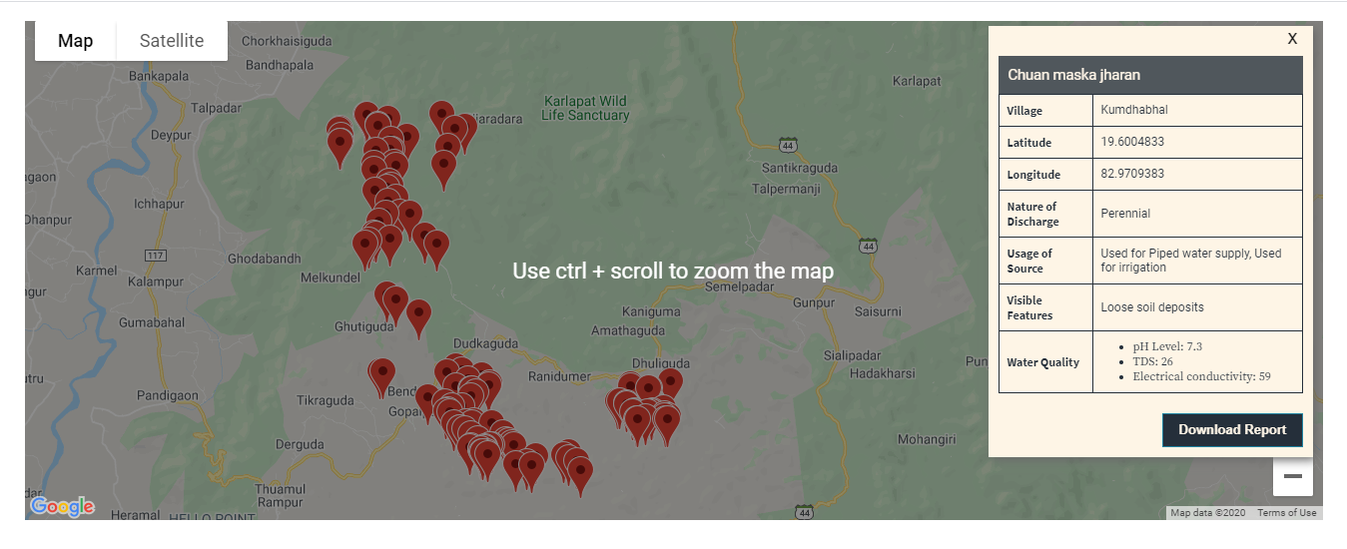

Spring Water Atlas

The Spring Water Atlas is an online repository of information on springs, spring-sheds and spring-scapes to strengthen springs management for addressing water scarcity issues for tribal communities in India. The tool is GIS-based, providing maps, spring health, water quality, and discharge, among other properties. The knowledge tool is hosted by the Ministry of Tribal Affairs and UNDP India. It can be access by the public here: thespringsportal.org.

Community Cadre

A community cadre of para-hydrologists, a mobile application and GIS technology converge to make the portal a rich storehouse of information on springs in India. Users can find information on the number of springs mapped and their health including water quality, discharge capacity and other physical, chemical and biological properties. 75 young men and women from 42 villages in 10 gram panchayats, have been trained and deployed as barefoot para-hydrologists, identify and map springs, and undertake measures for their rejuvenation and protection. Using the mWater application in their smartphones, these para-hydrologists collect data on the local hydrogeology and chemical properties of the spring source. This is then fed into the portal, Spring Water Atlas. The para-hydrologists were trained from November 2019 to February 2020.