In this edition of Earth Voices, environmental economist Mr. Hashim Zaman takes you to the Kalasha Valleys, in the heart of the Hindukush mountain range of Pakistan, where community-based mini hydropower (< 1MW) enables community-led initiatives and social enterprise development. For the indigenous Kalasha, this has helped build climate resilience as well as preserve their traditions and culture in one of the most isolated and inaccessible mountainous regions of Pakistan.

Note to readers: While our earlier Earth Voices case studies were developed using interviews, due to lack of direct access to the remote Kalash hydro communities at this time, we leveraged the next best option -- secondary research. We hope that you still find the article an insightful read on how community-scale hydropower has impacted the Kalasha.

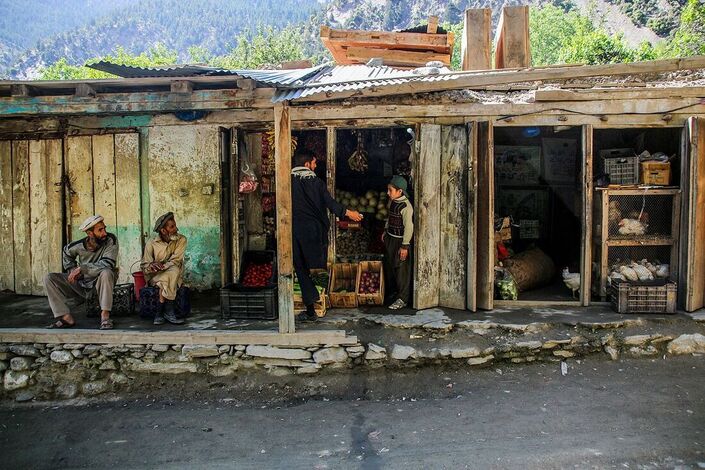

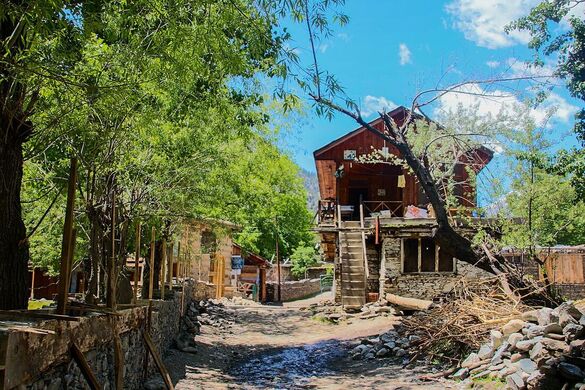

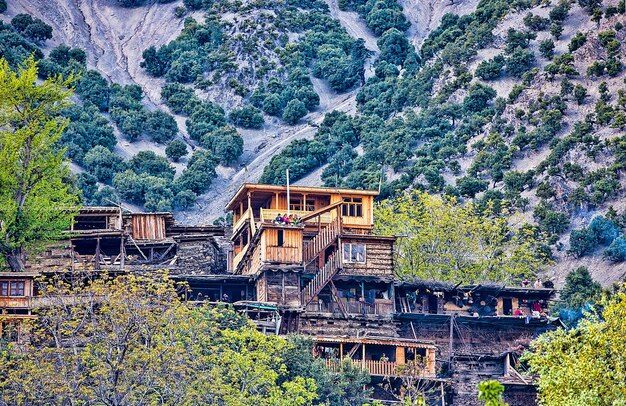

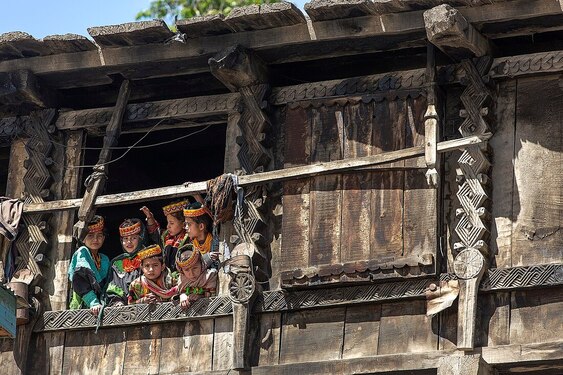

Tucked away in the mighty Hindukush range resides an ancient tribe known as the Kalasha. The indigenous communities of Kalash reside amidst the three mountain valleys of Bamburet, Rumboor and Birir, located in the Chitral District of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province of northern Pakistan. [1]

Kalasha girls celebrate during a festival. Credit: Kamal Zain

Kalasha girls celebrate during a festival. Credit: Kamal Zain

Kalasha family in Rumbur Valley. Credit: Sanam Saeed

Kalasha family in Rumbur Valley. Credit: Sanam Saeed

Forest products provide a major source of income for inhabitants of the valley. Wood, pine nuts, chilgoza, fruits, and medicinal plants are traded for much-needed income. [3] Moreover, the Kalasha see the forest as vital to their cultural survival and have fought to protect their rights to the land. For instance, from the 1980’s into the early 1990’s the Kalasha of the Rumbur Valley were involved in a 10-year court case to protect the forest for future generations. [5] A local who spearheaded the case stated that, “if we can turn the valleys into a reserve for future people, then the Kalash will survive for another 1,000 years”. [6]

| Nature continues to be central to the Kalasha’s spiritual beliefs and plays an important role in their daily lives. [6] Deforestation for timber and fuelwood not only disrupts the health of the watershed but triggers climate induced disasters such as glacial lake outburst floods (GLOF). Floods and erratic monsoon patterns lead to major destruction of crops and infrastructure, disruption in energy supply and loss of livelihoods. [7] |

Glacial floods have changed entire landscapes, posing serious risks around soil erosion, species migration and food insecurity. A local resident attributes the origin of these floods to melting glaciers in the region, explaining, “There are around four glaciers high up above in these mountains overlooking the valley. Glacial floods came down along with rainwater, carrying large boulders and we even saw large chunks of black ice”. [7] However, a disaster risk reduction expert from Chitral felt that torrential rainfall was the main cause of the flooding. [7] Similarly, a climate change expert attributed the cause of floods to El Nino (periodic warming of the ocean), which leads to erratic monsoon rainfalls, accelerates snow melt and subsequently triggers glacial lakes. [7] A local blamed deforestation and attributed the intensity of these floods to climate change. He explained, “It was still warm by the end of September this year, while the summers would usually end in August.” [7]

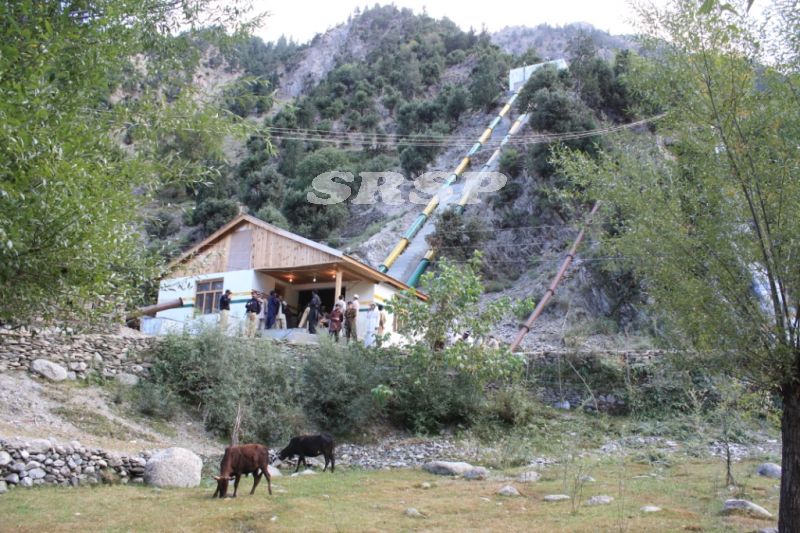

Building climate resilience and ensuring sustainable development requires retaining biodiversity and investment in nature-based solutions. Hydro mini-grids are a nature-based solution because their functionality depends on healthy forests. Thriving forests result in resilient catchment areas that provide maximum flow and erosion protection to the hydro mini-grid.

A healthy and connected community

| The Sarujalik mini hydropower system has 592 domestic and 111 commercial connections, providing electricity to almost 6,000 individuals across the valley. [10] Previously, the lack of reliable electricity services deprived the Kalasha of basic facilities, with negative impacts on their health and education. [1] The communities that were earlier using candles are now using telephones, refrigerators, and Internet facilities. [2] The local general stores are stocking their supplies in refrigerators, while uninterrupted electricity supply has enabled local businesses, such as welding and tailoring shops, to operate more optimally. [3] |

| Apart from monetary benefits, Kalasha are now enjoying a relatively healthier life. As some vaccines are temperature-sensitive and require cold storage, refrigerators have made it possible to vaccinate the population, and ensure a healthier and happier community. [1] Communication has also improved, as people are able to charge their phones at home and stay connected with their families, as well as access information and news from across the world. |

In these times of a global pandemic, community-scale hydropower has not only enabled online-distance learning, but has paved the way for a more informed community in one of the most isolated regions on Earth. Previously, teachers had difficulty conducting classes due to insufficient electricity in the school. Now, with improved energy access, there is evidence of more effective knowledge transmission and learning amongst students. [9] According to a schoolteacher, “students access new knowledge on the Internet and not only they become more informed, but they also share that information with us, and we learn from them too”. [9]

| The community-led hydropower has enabled schools to initiate an online enrollment system, allowing students to register for various national examinations. [9] Students are now able to access international research publications and supplement their existing knowledge with scientific and evidence-based research. [9] |

Mini hydropower and Kalasha women

Community-scale hydro has been a blessing for the women across the valley. Traditional wood-burning stoves have been replaced by more efficient electric cookstoves, and other electric appliances have reduced drudgery from laborious housework. [1]

SRSP’s bottom-up and community-driven rural development approach has helped the community build community-owned social enterprises, resulting in reliable income generation for the Kalasha. SRSP has ensured active community decision-making at all stages of MHP projects, from identifying potential sites and developing community structures, to keeping the system operational and participating in the cost-benefit sharing of the system. For long-term access to clean and green energy, committees have been set up to evaluate and provide connections to households, collect fees and ensure periodic maintenance of units. [10]

| SRSP has implemented 353 community-scale hydropower systems with a total installed capacity of over 29 MW, providing electricity to an estimated 900,000 individuals mostly in off-grid mountainous regions. [10] The founder of SRSP Mr. Masood ul Mulk says, “We do not see ourselves as energy generators but as an organization that gives hope to people who have been devastated by conflict and floods. Electricity is a way to harmonize and bring communities together. Providing light is just the beginning of the process of building up communities.” [11] Learn more about SRSP’s award-winning work in this video. |

As the global pandemic persists and we enter the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, climate-resilient and nature-based solutions become imperative. The role of community-scale hydropower in enabling clean energy access, uplifting livelihoods, and ultimately building resilience is vital in the context of the global climate crisis. We can learn from and be inspired by the resilience of indigenous local communities such as the Kalasha, and strive towards a more equitable and a sustainable future.

[1] http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/zh/960841551256802132/pdf/Indigenous-Peoples-Planning-Framework.pdf

[2] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4570283/pdf/main.pdf

[3] http://kp.gov.pk/uploads/2019/04/IPPF_Pub_Disclosure3.pdf

[4] https://cmjournal.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s13020-018-0204-y.pdf

[5] http://www.icwa.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/CVR-27.pdf

[6] http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/shared/spl/hi/picture_gallery/05/south_asia_kalash_spring_festival/html/3.stm

[7] https://climate.earthjournalism.net/2015/12/03/kalash-valleys-struggle-to-survive-post-floods.html

[8] https://www.pk.undp.org/content/pakistan/en/home/projects/Glof-II.html

[9] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wDFCdius3KQ&feature=emb_logo

[10] http://www1.srsp.org.pk/site/alternate-energy-new/

[11] https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2015/jun/12/pakistan-electricity-village-micro-hydro-ashden-award

Content support from Atif Zeeshan Rauf, Sarad Rural Support Programme

Editing support from the HPNET Secretariat