Small-scale hydropower also presents great potential for ecosystem restoration in Madagascar. Healthy watersheds are critical to sustainable community-based hydropower, as mature forest cover ensures consistent stream-flow, mitigates erosion, and builds resilience against the impacts of climate change. As such, hydro mini-grids are a nature-based solution that promotes watershed strengthening. Investment in nature-based solutions like small-scale hydro can play a critical role in building climate resilience and safeguarding biodiversity in Madagascar, where more than 90% of original forests have been lost.

One of the leading small-scale hydro implementation organizations in Madagascar is the Association des Ingénieurs pour le Développement des Energies Renouvelables (AIDER). Read on to learn about AIDER’s efforts to advance small-scale hydro in Madagascar.

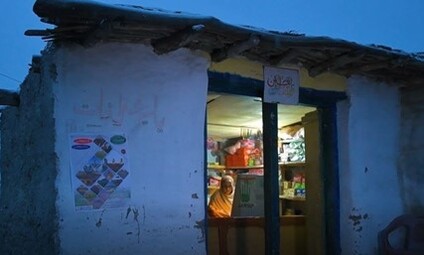

AIDER has built eight MHPs, ranging from 7.5 kW to 100 kW, electrifying a total of about 450 households in rural municipalities of the Analamanga and Atsimo Andrefana regions. Five of the projects are owned and operated by AIDER. All of the systems use turbines that have been locally manufactured by AIDER, thereby having generated local employment. In addition to providing reliable electricity to households, the MHPs power town halls, police stations, clinics, churches, schools, and street lighting.

Since 2009 AIDER has carried out approximately 30 studies for micro hydropower projects (MHPs), including hydrological studies. In 2018 AIDER began collaboration with the Swiss Resource Centre and Consultancies for Development (Skat). On behalf of GIZ’s Renewable Energy Electrification Project (PERER) in Madagascar, Skat partnered with AIDER to conduct the following.

- Feasibility of study of the Amabatotoa site, where the options of a 100 kW off-grid project, 2.3 MW grid-connected project, and 6 MW grid-connected reservoir project in the Upper Matsiatra Region

- Feasibility study of the Ivato off-grid site of 100 kW in the Amoron'i Mania Region

- Detailed study of the off-grid Sahandaso Mini Hydro Project of 240 kW in the Atsinanana Region, including developing the MV line plans, single line diagrams, design calculations and cost estimates

AIDER carried out hydrological analyses, topographical surveys, installation and operation of the gauging stations, installation of pressure probes, and recording tables with iridium antenna for auto data transmission. It also conducted flow measurements and analysis using the propeller method, conductivity meters, and an acoustic doppler current profiler (ADCP).

AIDER and SKAT are currently collaborating with CEAS and UNDO to develop a detailed design study for the development of the Andriambe mini hydro project, having a potential of 225 kW and located on the Nanangainana River in Mandialaza.

The project aim is to provide clean and affordable electricity to three villages, in terms of household needs, critical social infrastructure, and productive end uses, such as carpentry workshops, feed mills, metal workshops and food processing.

Ginger processing presents a particularly promising opportunity to generate income in the villages. Ginger is currently sold as a raw product to passing traders at a very low price. Affordable electricity will enable the production of a higher-value product.